| Journalism

Was Ramona Real? How a Book Became More Than a Legend Was Ramona Real? How a Book Became More Than a Legend

Cut to Bob Dale - An off-camera chat with the bow-tied veteran of San Diego television Cut to Bob Dale - An off-camera chat with the bow-tied veteran of San Diego television

Salvation Row - An uneasy Episcopalian hears the word on Imperial Avenue Salvation Row - An uneasy Episcopalian hears the word on Imperial Avenue

Lester Bangs -The Hardback Lester Bangs -The Hardback

Dots on the Map - Heading East on Old Highway 80 Dots on the Map - Heading East on Old Highway 80

Silents Were Golden - Why early filmmakers zoomed in on San Diego Silents Were Golden - Why early filmmakers zoomed in on San Diego

Where Wild Things Were- Something is lost when something is built Where Wild Things Were- Something is lost when something is built

One for the Zipper- The quintessential carnival ride must bring chaos to the calm center of the soul One for the Zipper- The quintessential carnival ride must bring chaos to the calm center of the soul

Deadhead Redux - No one knows for sure why Grateful Dead fans have such a drive to communicate with each other but they do-and they’ve turned Blair Jackson and Regan McMahon’s “The Golden Road” into the most successful fanzine in the history of the form. Deadhead Redux - No one knows for sure why Grateful Dead fans have such a drive to communicate with each other but they do-and they’ve turned Blair Jackson and Regan McMahon’s “The Golden Road” into the most successful fanzine in the history of the form.

The Last Anniversary - An Altamont Memoir The Last Anniversary - An Altamont Memoir

Desolation Row -The lonesome cry of Jack Kerouac Desolation Row -The lonesome cry of Jack Kerouac

Faster Than a Speeding Mythos: Superman at 50 - Superman at 50: The Persistence of a Legend Faster Than a Speeding Mythos: Superman at 50 - Superman at 50: The Persistence of a Legend

When Art is No Object -The Eloquent Object - At the Oakland Museum, Great Hall, through May 15. When Art is No Object -The Eloquent Object - At the Oakland Museum, Great Hall, through May 15.

“He Wasn’t Dying to Live in L.A.” - Intrepid Journalist’s Last Dispatch Before His Collapse “He Wasn’t Dying to Live in L.A.” - Intrepid Journalist’s Last Dispatch Before His Collapse

Search for Honesty in Post-war Life - Plenty Search for Honesty in Post-war Life - Plenty

Armageddon Averted: Where Will You be on August 16. 1987? - Inside Art Goes to the Frontiers of the Mind Armageddon Averted: Where Will You be on August 16. 1987? - Inside Art Goes to the Frontiers of the Mind

Of Speckle-Faced Rats and Supernovas - Michael McClure Of Speckle-Faced Rats and Supernovas - Michael McClure

George Coates - The Physics of Performance and the Art of Iceskating George Coates - The Physics of Performance and the Art of Iceskating

No Escape from the SOUNDHOUSE - Maryanne Amacher No Escape from the SOUNDHOUSE - Maryanne Amacher

A Pynchon's Time A Pynchon's Time

Grants - State of Art/Art of the State Grants - State of Art/Art of the State

Poetry from Outside the Pale - Allen Ginsberg Poetry from Outside the Pale - Allen Ginsberg

Once Upon a Time - In Berkeley Once Upon a Time - In Berkeley

The poet from Turtle Island - Gary Snyder The poet from Turtle Island - Gary Snyder

Noh Quarter

Joyce Jenkins and the Language Troubles Joyce Jenkins and the Language Troubles

Philip Whalen Philip Whalen

|

|

When Silents Were Golden

Why early filmakers zoomed in on San Diego

Story By ROGER ANDERSON

September 7, 1989

I was born and raised in the East County, and — strange as it may sound to those who weren't —there are few things that interest me more than authentic visual documentation of daily life in that region during its early years. I'd probably walk across town during a heat wave just to get a look at a water-stained photo of downtown El Cajon taken, say, in 1911. And if, instead of a still photo, the visual documentation in question were an old movie, there is little I wouldn't do for the chance to see it.

So today, I'm at the La Mesa Historical Society, about to look into the past in an almost literal sense. Donna Regan, president of the society, and Jim Harwood, a society member, are scurrying around setting up a projector and screen in the restored dining room of the society's museum/ headquarters, a charming Edwardian residence at 8369 University Avenue, built in 1908 by the Rev. Henry A. McKinney. They're preparing to show me a rare print of a one-reel silent film made in Lakeside in 1911.

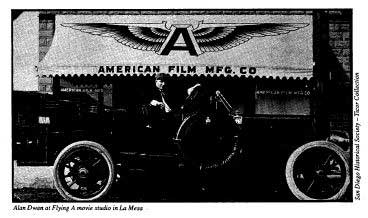

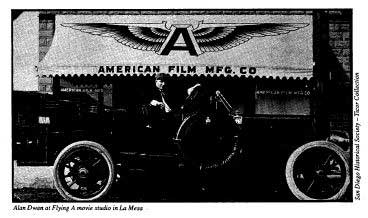

The film, entitled Three Million Dollars, was directed by Alan Dwan, who had a very long and illustrious career as a film director. He made such well-known talkies as Heidi, starring Shirley Temple, and The Iron Mask, which starred Douglas Fairbanks. In 1911, Dwan worked for the Chicago-based American Film Manufacturing Company, popularly known as Flying A, after it’s winged A company logo. The Flying A crew made films in San Juan Capistrano, then in Lakeside and La Mesa, before moving on to Santa Barbara. During the company's East County stint (1911-1912), Flying A ground out hundreds of westerns, comedies, and documentaries at the rate of two a week.

Since it never occurred to anyone in those days that these pieces of quick-and-dirty nickelodeon fodder would be of the faintest interest to posterity, no effort was made to preserve them; today, only a few exist.

Those few are, as it turns out, of limitless interest not only to film-history buffs but to average citizens like me, fascinated by earlier, simpler times. For the last few years, I've tried to track down a locally made silent movie I heard rumors of, with the intriguing title Juanita of El Cajon — doubtless one of the many ripoffs of Helen Hunt Jackson's wildly popular "Ramona" story that were essayed in almost every medium during the early part of the century. Unable to locate Juanita, I have managed at least to track down this print of Dwan's one-reeler. While Regan and Harwood fumble with the projector, I'm having a hard time containing my eagerness.

"One thing I don't quite understand,” Jim Harwood says while carefully (and fruitlessly) threading film for about the tenth time. "What were Dwan and these other directors doing all the way out here in the first place?"

Regan herself has made quite a study of this and other film-related matters; she even interviewed Dwan shortly before his death in 1981, at the age of 96. But my zest for the subject causes me to butt in. "For one thing," I explain, "it was harder for patent enforcers to find them."

Most people are likely to assume that at the time of the Big Bang, Hollywood had already been designated the movie capital of the universe. But there was a time, early in the century, when Fort Lee, New Jersey, was the town where celluloid stars were born. Then, toward the close of the century's first decade, the film industry, like the country's population, began to drift west.

The reasons for this shift were twofold. First was the question of patents. A number of the larger motion picture producers, annoyed by competition from a host of shoestring movie companies, got together and formed the Motion Picture Patents Company, which — legitimately or not — claimed to hold the rights to the possession and use of movie-making technology. Under this heading, they included not only cameras, film, and projectors, but the Latham loop, which was not even a piece of technology per se but merely the loop you had to create in a piece of film to get it to run through the projector without tangling. (A mastery of this technique might stand Regan, Harwood, and me in good stead right about now with the recalcitrant projector.) The patents company daily sent out its operatives — hooligans and private dicks — to sabotage the cameras and film of competing companies. So smaller companies like Flying A started moving to the open spaces of the western U.S. to make it more difficult for the enforcers to track them down. If you were a patent enforcer on assignment in Fort Lee, New York, or Chicago, all you had to do was get on a streetcar with a revolver in your pocket, get off at the targeted movie company's address, and let fly a fusillade of bullets at every piece of movie equipment in sight. On the other hand, if the company in question was working in rural Arizona or California, you had to hire a mule team and a guide to track them down, after getting out to the West Coast, by laborious rail travel, in the first place.

The second reason for the westward migration was the superabundance of unbroken sunlight and a rich variety of scenery — beaches, mountains, deserts, forests, and canyons. And reliably clear days were important, since the sun was the set illuminator of the first and last resort in those early days.

Indeed, J. Gordon Russell, a publicity flack for Pollard Picture Plays, wrote in the San Diego Union on January 1, 1917:

In this respect, San Diego has few rivals — either in this or foreign countries. During my years of experience in the motion picture business with various companies, many of which have made pictures in Cuba, Florida, Japan, Hawaii and Italy, never have I seen a spot where the light was so brilliant, consistently even, abundant and easily adapted for moving picture photography as it is in San Diego....

With her mountains, meadows, parks, ravines, beaches, strand, desert, valleys, islands, variegated coast lines, beautiful homes, handsome business blocks, unsurpassed roads and wonderful Exposition, San Diego more completely meets the requirements for "variety of outdoor scenery" than any other city in the old or new world.

The first wave of film production migration sent a foam of crews and cameras spilling all over California, from Coronado to Niles, just south of Oakland (where the Essanay company made its groundbreaking Bronco Billie western series and Charlie Chaplin did some early fine-tuning on his Little Tramp character). Until 1914 or so, the role of movie capital of the universe was up for grabs. In many respects, El Cajon or Santa Barbara were just as likely candidates for the job as Hollywood.

But only three years later, when Mr. Russell was committing his flattering impressions to paper, the die was pretty well cast. Hollywood, with all the resources of Los Angeles, the largest metropolitan area in the region, at its disposal, was just about set as the cinematic center of the U.S. The presence there, by 1917, of such highly influential and successful moviemakers as D.W. Griffith, Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford, and Douglas Fairbanks put a lock on it. But even into the '20s, film crews would still pop up in the San Diego area with some frequency.

Many of these companies were not only small-time but positively fly-by-night. While Flying A, Ammex, Essanay (which shot some of its Bronco Billie films in La Mesa before moving on to Niles), Jim Aubrey Productions, and the Nestor Film Company actually produced movies, others — like the El Cajon Film Company and S-L Studios -appeared, set up shop, cajoled the citizens and local governments into lavishing hospitality on them, and disappeared. The La Mesa/Grossmont area seems to have been a particular target of such designs.

On December 2, 1916, the EL Cajon Valley News printed the following account:

A pretentious plan has been drawn up for the motion picture producing plant and grounds of the Empire Feature Film trust, which closed a deal last Wednesday for forty acres of land at Murray Hill, just north of Grossmont.

The agreement in the transfer of the property from James A. Murray to the film concern ... stipulated that the motion picture producers shall expend at least $20,000 within the next six months.

The plans of the Empire people contemplate the production of some of the most elaborate motion picture films ever attempted in this country.... The main building, which will be 360 feet long, will show many different periods of architecture. Among them will be sections of the Renaissance, Gothic, Roman, Grecian, Elizabethan, Oriental and Mission types. The stage will be 200 feet long and 80 feet wide. The buildings around the stage will include a costume making department, property rooms, scenic studios, dressing rooms, a fire department, hospital and laboratories, printing rooms and projecting studios.

In addition to the studios there will be an administration building in the Elizabethan style, embodying a large number of offices, an assembly hall, library and museum. The assembly hall is to have a moveable stage and will be used for lectures, rehearsals of plays and such entertainments as the management will give for their employees and guests....

There will also be a club house where the players can engage permanent quarters. There will be a large dining room and a swimming pool, which [is] planned to be built below the lake.

Today, you will search in vain through newspaper files and film history books for mention of the great movie deeds wrought by this collaboration between Empire, the City of La Mesa, and the estimable James Murray.

In 1922 — time enough, one assumes, for memories of the Empire Feature Film debacle to have faded — a studio calling itself S-L, after owners Arthur H. Sawyer and Bert Lubin, appeared in the East County with another scheme. (Lubin, who had been the proprietor of a film company in Coronado, seems to have served here as a silent partner; almost no mention of him is made in accounts of the episode.) On September 8 of that year, the following article was printed in the El Cajon Valley News:

Construction work on the new moving picture studio at Grossmont was begun Monday morning, September 4.

A crew of about 40 men ... with mule teams, about a half dozen Fresno scrapers, and several plows, has been busily employed all this week grading and leveling the site for the first unit....

This first unit of the studios, which is to cost $50,000, is being built by the people's money, both local and in San Diego, and has not been directly financed by the S-L corporation. This amount was the inducement asked by the S-L corporation for bringing their project to this territory. Stock in the company was sold to obtain this sum.

The site selected for the first unit is the tract immediately north of the pavement leading over Grossmont and just east of the dirt road which leads to the Eucalyptus Reservoir....

The building is to be 300 X 90 feet in dimensions.... The other nine units are to be built ... farther up the hill to the east.

It has also been rumored that the company has secured options on about 1,800 acres of land adjacent to the studio site for the purpose of erecting thereon homes for the employees of the studio and building there another Universal City.

Only a couple of months later, on November 19, S-L was ready to unveil the new studio by laying on a day-long festival of speeches, ceremonies, and appearances by movie stars. On November 24, the News printed the following account of the event:

Attended by an unusual galaxy of moving picture celebrities from Los Angeles and Hollywood and a welcoming crowd of between 15,000 and 20,000 San Diegans, the formal dedication exercises of the first big unit in the $1,000,000 S-L Studios moving picture plant at Grossmont was celebrated last Sunday afternoon. The laying of the cornerstone, the first stage of the plant, said to be designed as the largest equipped in the world when the three companion stages are completed, together with the administration building, received the same ovation that was given to Arthur Sawyer ... the first moving picture producer who has shown his faith and courage in the belief that Grossmont is to be the final mecca of the great industry by actually building a plant in southern California.

To say that Grossmont was the center of filmdom Sunday is no exaggeration. Hundreds traveled on a special train over the S.D.&A. railway direct to the studio site.... Mayor EW Porter of La Mesa made the address of welcome.... F.M. White, president of the Manufacturers' and Employers' association, who is a stockholder in the S-L studios, said: "The businessmen of San Diego are beginning to realize the value of ... Arthur H. Sawyer. They realize the value of S-L Studios and believe in its future. We are going to do everything we can to make it success...."

When Sawyer took his place on the speaker's stand, he received an ovation that lasted several minutes.... He told how Colonel Ed Fletcher more than a year ago had interested him in the idea of making tests that later proved Grossmont the ideal location for a moving picture plant of this country. He said: "This is the first of a series of at least four units, which ... will make this the largest rental studio in the world."

If this seems to have overtones of the plot from The Music Man, in fact S-L Studios never did produce any motion pictures worth speaking of at its Grossmont plant. And a couple of years after the opening, the redoubtable Col. Ed Fletcher, seminal land and development mogul of the East County during these years, purchased the studio from S-L with the idea of renting out the facilities (which he renamed Grossmont Studios) to wandering film companies. A few films were eventually shot there; but by the early '30s, the entire enterprise was grinding to a halt. The plant was sold, transformed into a roller-skating rink, then a saloon, and burned to the ground in 1934.

The ill-starred S-L facility is now even the subject of debate over exactly where this "final mecca of the great industry" was situated. A 1983 Daily Californian story suggested that the studio was built behind the plot of land where the La Mesa branch of Anthony's Fish Grotto has stood for decades (at 9530 Murray Drive). But one long-time East County resident wrote the paper to quarrel with this finding: "The old Grossmont Studios building was not located near Anthony's, unless the restaurant has moved in the last couple of years.... [It]i was located west of Fuerte Drive about 100 yards from the crest of the hill on the north side of the highway. The acoustics in that old barn were terrible and after it became a barroom and dancehall it even smelled bad. I distinctly remember the urinals running over every time I was in there, which was quite often, even though I was only nineteen. We started early in those days.”

Seven years later, instead of being the scene of flimflam studio construction, the El Cajon Valley was used for location shooting of a Hollywood film. Once again, the News was on hand to report the event. It related in its issue of May 31, 1929:

The Columbia Pictures corporation of Hollywood is making elaborate preparations for filming at El Cajon a new picture that will probably be known as "Flight" ... and will have as its stars Jack Holt and Ralph Graves.

These preparations include the construction of the front of a building ... on the south side of Chase avenue ... and also the installation of an aviation landing field on the 20 acres of land ... lying north of Chase avenue and west of Magnolia.

It is expected that the members of the cast will arrive from Hollywood [Friday]....

The structure on Chase avenue ... is to represent the front of the headquarters of the aviation division of the marine forces in Nicaragua, as the entire picture purports to be a representation of the actual occurrences in that country during the occupation of the marine forces.

Three companies of marines from the base in San Diego and a squadron of about ten planes from North Island will be used.... The people of this vicinity will have the movie action, but whether it can be at close range or not is to be decided by the management. However, the planes landing and taking off west of Magnolia avenue.and between Washington and Chase can not escape observation if it were desired.

The report ends with an account of an incident that had happened between two groups of extras during filming near Los Angeles:

At El Monte last week there was put on an attack of Nicaraguan "insurgents" upon a stockade occupied by U.S. forces. Three companies of marines went out to represent the latter and an aggregation of about 500 Mexicans and Indians picked up in San Diego represented the insurgents. They were armed with rifles loaded with blanks and had orders to cease firing when they arrived within a few yards of the defenses. In their zeal and patriotism, however, they forgot or disregarded their orders and rushed forward and peppered the marines at close range with blank cartridges, which are supposed to be harmless but when fired at a distance of only a few yards inflict annoying hurts. This peeved the marines and they swarmed out of the stockade to get revenge. For a few minutes ... it looked as if there might be some real action in the camp, but the boys were persuaded to exercise moderation, patience and a forgiving spirit and peace prevailed.

The director of the entire project is Mr. Frank Capra.

Of course, at this point, Frank Capra had yet to direct his most famous works, It's a Wonderful Life, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, and his other popular, feel-good motion pictures. He was, in 1929, Frank Capra, maker of silent-film military epics. Capra soon learned that shooting a movie in the El Cajon wilderness wasn't going to be easy. On June 7, the News informed its readers that the film project had met with a setback:

The structure erected on the south side of Chase avenue with such care by the Columbia Pictures Corporation last week was completely wrecked by a whirlwind last Friday afternoon. Nothing was left of it but a mass of debris that will render reconstruction more difficult than if the ground was unoccupied. The structure was built to represent the front of the headquarters building of the aviation forces in Nicaragua. It was ... so narrow that, without proper braces, it was easily overturned by any strong gust of wind, and the wind came Friday.

But on June 21, the set having been repaired, the News was able to provide its readers with a full account of the project's local denouement, under the headline "Movies — Talkies Made In El Cajon Valley":

The work of making movie and talking pictures by the Paramount Pictures Corporation in El Cajon got under way the first of this week and the grounds on the north side of Chase avenue have been for several days presented a busy scene. There have been more than a hundred people employed, including the leading actors and actresses and the workmen, and most of them have been entertained at the local hotels. Mrs. Knowles had 107 at dinner Monday evening and about a hundred Tuesday evening.

Monday night presented a free show for all residents and the result was that parking space along Chase avenue for nearly a quarter of a mile each way from the grounds was all occupied. Somebody overlooked a bet, for he might have collected a dime from each car owner for parking. Nobody thought of that, however, and so the public escaped that expense.

There were 11 airplanes ranged along the side and half a dozen or more powerful spotlights that were directed upon different parts of the grounds. In a general way it all suggested a circus with the exception of the "big top" and the animal sounds....

Any one looking about is impressed with the great amount of work that is required in the operation. Wires must be laid, electric generators operated and cameramen and helpers served.... Then after a "shot" is made it may have to be all done over again because of some little defect in the picture or synchronizing the scene with the sound of the voices...The casual uninformed visitor gets little out of it, for ... the people employed on the job are too busy to take him on for instruction. The outfit was packing up and leaving Wednesday.

Flight premiered nationwide at the beginning of 1930 and played the La Mesa Theater on January 25, 26, and 27 of that year.

I have been looking for a copy of that early Capra film, but so far, my researches turned up nothing. And that's another reason why today I'm sitting in near-darkness at the La Mesa Historical Society, waiting to be shown a movie that's not nearly as ambitious but which is, at least, a couple of decades older and promises to show scenes of East County from a time when it was still in its cowboy days.

And after all, Alan Dwan does bear comparison with Frank Capra as an important figure in the evolution of American movies. And, too, when Dwan arrived in the East County he was a neophyte director, age 26, and his great contributions to movie culture were still ahead of him. Trained at Notre Dame as an electrical engineer, he had entered the film world more or less through a side door: one of the heads of the Essanay movie company discovered him in the Chicago Post Office, where he was working on a new lighting system meant to ease the strain on the eyes of postal workers required to sort envelopes all day and was hired away to design lighting for film shoots. He soon traded in his wire snips for a pen and began working as a scenarist for Essanay. Then Flying A happened along and offered to double his salary if he'd come and work for them. After a brief stint in Tucson with a production unit in 1909, Dwan was sent to San Juan Capistrano, where one of the Flying A units seemed to be foundering. When Dwan arrived, he learned that the unit's director had been off on a bender for some time. Informing the Chicago office of this, Dwan was ordered to take over as director himself.

As Dwan related to Peter Bogdanovich in his book Alan Dwan: The Last Pioneer, "So I got the actors together and said, 'Now, either I'm a director or you're out of work. And they said, 'You're the best damn director we ever saw. You're great.” I said, 'What do I do? What does a director do?' So they took me out and showed me....

"The first thing they did was give me a chair and say, 'You sit here.” And they gave me a megaphone and said, 'You yell through this. And I said, 'What do I yell?' You yell, "Come on" or yell "Action." When you say that, the cameraman will start turning the camera, and just say "Cut" when you want him to quit. And then you wave a flag or something and we'll ride over the hill, or we'll walk in and do our scene.’ "

Having thus mastered the rudiments of film directing, Dwan decided to move the unit farther out of reach of the patent enforcers. He and his crew ended up in Lakeside, where he took up residence at the Lakeside Hotel and billeted his crew members in local homes. They set about producing one-reelers in a virtually unending stream. He later described his filmmaking praxis for Bogdanovich:

"We used horses and rigs at Lakeside. I'd pile everyone into two buckboards, a ranch wagon for our equipment, the cowboys on their horses — the actors too if they were riding in the picture — and off we went out into the country to make a picture. On the way out, I'd try to contrive something to do. I'd see a cliff or something of the sort. I had a heavy named Jack Richardson, so we'd send J. Warren Kerrigan, the leading man, up there to struggle with Richardson and throw him off the cliff. Now, having made the last scene of the picture, I had to go backwards and try to figure out why all this happened."

After several months of working in Lakeside, Dwan realized he was running out of extras; nearly every resident in town had appeared in several of his movies. So in August of 1911, he moved operations to La Mesa. Since La Mesa was a bit closer to the beaten track than Lakeside, problems with the patents goons arose again:

"One day in La Mesa,” Dwan told Bogdanovich, "a rough-looking character got off the train and looked me up. He said he was sent out to make sure me and my company got out of there and quit making pictures. Well, we took a walk up the road to talk it over. I hadn't been out of college for too long and was, in good physical shape. So I wanted to get him far enough out of town to see if I couldn't beat his brains out. We stopped at a bridge over an arroyo where people had thrown some tin cans. There was a bright one sitting out there, so to impress me he whipped a gun out of his shoulder holster and shot at the can and missed it by about five yards. I pulled out my gun and hit the can twice, and that afternoon he left town. Also he was accompanied to the depot by my well-armed cowboys. From that time on we were never molested."

Later, Dwan moved his crew up to Santa Barbara, and eventually he left Flying A for the filmmaking big leagues. But as a memorial of his salad days in the East County, Dwan left a wad of one-reelers with titles like The Poisoned Flume, The Trail of the Eucalyptus, The Yiddisher Cowboy, The Cowboy Socialist, The Relentless Cowboy, Justice of the Sage, The Winning of La Mesa, The Land Baron of San Tee, and Barney Oldfield's Race for a Life (in which the famed race-car driver portrayed himself). Most of these nitrate-stock movies have since been rendered down to their constituent parts by the passage of time. But at least one original print of Three Million Dollars still exists, though in somewhat tattered form, in the possession of the La Mesa Historical Society.

But now Donna Regan and Jim Harwood have succeeded in reinventing the Latham loop, the projector is humming, and silent scenes of pre-World War I Lakeside are flickering on the screen like beams of light from a long-dead star.

Once the film is rolling, it becomes perfectly obvious why neither Dwan nor anyone else ever deemed it worth going to any special lengths to preserve. Its storyline and plot development show every sign of having been made up on the seat of a buckboard only moments before the cameraman was instructed to start cranking. It is reminiscent of the plays children dream up and act out on the spur of the moment, its elements jammed together any which way, and all thoughts of dramatic or emotional coherence left entirely out of account.

The idea is that the ranch-owning father and mother of the girlish heroine (played by Pauline Bush, who later became Dwan's wife) learn that their daughter is eligible to receive a $3 million inheritance if she is married within the month. Earlier, Papa — whose acting resembles the Italian comic-opera sort —had put an end to a flirtation the girl was having with a local storekeeper (J. Walter Kerrigan, Dwan's leading man). And although the old fellow is now hell-bent on coercing his daughter into marrying just about anyone at all, it never occurs to him that he could save everyone a lot of bother by simply giving his blessing to her match with the storekeeper. Instead, he persuades some cowboys to (1) kidnap the girl and tie her up, then (2) kidnap the first eligible man they come across. Papa will then provide a clergyman of some kind to bind the two youngsters in holy matrimony, against their will. So the cowboys kidnap the girl, tie her up, and ride off.

Of course, the first eligible man they encounter is Kerrigan, the storekeeper. Before too long Kerrigan and Bush find themselves tied up together and left alone while the cowboys go off to bring back Papa and the clergyman. The pair untie themselves, begin to run off, then suddenly realize they only have to play along with the scheme to win each other and the $3 million. Papa somehow fails to recognize Kerrigan, the couple is married, everyone's happy, and the movie's over much more quickly than it got under way.

The whole thing requires only about 10 or 12 minutes to screen; and since it took about three times that long just to get the projector working properly, it makes sense that Regan, Harwood, and I rewind the film and play it again. This time around, the nonsense of the story is even more apparent; but so, too, are the film's examples of what were in those days innovative narrative techniques. (The Great Train Robbery in 1903 had broken the cinematic and narrative ground that Dwan and his colleagues were now tilling.) The opening scene, in which Bush and Kerrigan flirt inside the store, represents something at that time brand new in the realm of storytelling. Customers sidle in and pick through merchandise; then two or three little boys enter and steal a watermelon while Kerrigan is oblivious. These peripheral characters are able to pass in and through the action in an unobtrusive and believable way that can only be compared to real life.

The scenes in which Bush, then Kerrigan and Bush together, are left bound by an exterior wall serve as more examples of what film in those days was allowing a storyteller to do for the first time. Each shot is set up so that the wall takes up the right half of the screen; the left half comprises a deep perspective of fields. Intimate action between the two lovers unfolds in front of the wall, as if on a tiny stage; the world at large flows in through the fields as gangs of cowboys charge up at key moments to move the story along a notch. In each shot, you see the full gamut of scenic potential that the movies were in the process of ushering in, from close-up immediacy on the one hand to full epic action on the other.

Disappointingly, the movie shows no scenes of recognizable Lakeside streets or structures that I can compare with the town as I've known it during my lifetime. But it does show something more evocative: vistas of wild grass and brush, granite outcrops, cloud-streaked skies, winding dirt roads. Here is the Southern California landscape as it is, beyond the towns and freeways and housing developments — a murmurous expanse of almost-desert, silent fields where dreams of the future come to life. For a moment, sitting in the darkness of the La Mesa Historical Society as the images ratchet across the screen, I forget that I'm watching a movie and believe that pictures of a familiar yet long-gone world are being beamed in through a hole in time, that the tatters and exaggerated contrasts of the ancient print are nothing more than static seeping in as the images make their long journey through the years.

back to top

|