|

|

Deadhead Redux No one knows for sure why Grateful Dead fans have such a drive to communicate with each other but they do-and they’ve turned Blair Jackson and Regan McMahon’s “The Golden Road” into the most successful fanzine in the history of the form. Story By ROGER ANDERSON I'm not a Grateful Dead fan myself. As far as I'm concerned, you can go the rest of your life thinking of "Deadheads" as tie-dye-clad youngsters and aging hippies forever whacked out on beer and mescaline, and forever (or seemingly forever) camped in front of Kaiser Convention Center or the Greek Theater banging on acoustic guitars and selling each other T-shirts and jewelry. But the fact is that this image is very oversimplified.

Take Blair Jackson and Regan McMahon, editors and publishers of a magazine called The Golden Road. Nobody is going to mistake these two 35-year-olds for wandering troglodytes in search of cheap musical and social thrills. Blair cut his journalistic teeth working on an underground paper in high school, and conceived a fanatical devotion to the Dead around the same time. Later he studied journalism at UC Berkeley, specializing in music criticism. In '78, when Blair left the school of journalism to take a job at BAM magazine, he met Regan, a student of literary criticism with a degree in French, who was also working as a BAM editor. • • • By the time Blair and Regan came along, Grateful Dead culture was, of course, already a long-lived and highly developed phenomenon. Moreover, Deadheads have been communicating with each other in print since the early '70s, when the band's Skull and Roses album was released with a legend on the cover asking "Deadheads" to come forward, proclaim themselves, and subscribe to a newsletter that the band's staff was then putting out. "It was a four-page newsletter with art by Robert Hunter, Garcia's lyricist, and with strange doodles and non sequitur things," Blair explains. "And it also featured information about the band, like `Here's a diagram of our new monster sound system,' or 'Here's where the Grateful Dead dollar went last year,' and they'd break it down into a pie chart—this much went to band salaries, this much to the road crew, etc." Publication of the newsletter ceased after a few years, but it's been succeeded since then by any number of unofficial, mainly amateur publications on the same general theme. In 1984, the main thing going on in this sphere was a magazine out of New York called Relix, which is still being published. Blair and Regan make few bones about the fact that it was in part the editorial deficiencies of Relix that prompted them to begin putting out The Golden Road.

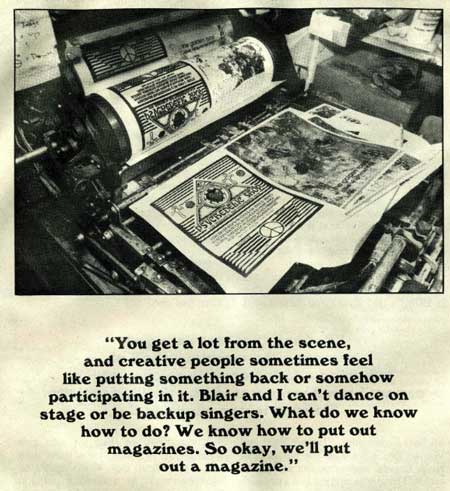

BLAIR: "Basically, we started doing the magazine because we wanted to have an outlet to explore issues relating to the Dead on a regular basis. Since we were interested in so many levels of the Dead experience and knew other people who were, we figured a lot of people out there would be interested. Also, I had never particularly liked Relix, and I felt that being in the Bay Area, being in the music business, having some slight connection to the Dead scene, and being interested in journalism and magazines sort of put us in a good position to do something fun and intelligent. Not to harp on this, but I felt what Relix was missing—apart from general journalistic quality—was the whole intellectual end of it, plus the really funny side of it. We've always tried to have humor. And I think we're pretty self-deprecating, and we certainly don't fawn over the Dead that much. We criticize them, and we joke about them all the time. They can take it; they're funny themselves. So I just thought the whole thrust we could bring to it was different from anything that was already out there." REGAN: "You get a lot from the scene, and creative people sometimes feel like putting something back or somehow participating in it. Blair and I can't dance on stage or be backup singers... " BLAIR: "We're not artists, so we can't make T-shirts." REGAN: "You know, there are people who say, 'Hey, this is great,' so they make T-shirts or jewelry or bumper stickers or whatever. They want to reflect back what they've got, what turned them on, and then use their own talent to take it, mutate it, and put it back out there for other people in the scene to enjoy. Since we're writers and editors, this is our outlet. What do we know how to do? We know how to put out magazines. So okay, we'll put out a magazine." BLAIR: "And this is an especially good area to put out a magazine of this kind. After all, the Grateful Dead have been operating out of this area for 23 years now, and the Dead scene has always had its tentacles out—it's in Humboldt, it stretches all the way up through Oregon, it's in Eugene, it's in Portland . . . " REGAN: "It's in Garberville." BLAIR: "Right, the pot-growing belt. To this day there are strong remnants of the hippie movement or whatever you want to call it.... REGAN: "The counterculture." BLAIR: "The counterculture is still firmly entrenched in this area, and the Grateful Dead have always been the band for that culture. And most of these people—contrary to what you may read in Newsweek—haven't really changed their world view particularly since the '60s. So there's always been a very strong hippie influence in this area, whereas places like Boston or New York don't have that current going along, since after 1972 it really did die out in urban areas back East. So if you go to shows in the East, it's much less hippie-ish. The ambience is different. It's a younger crowd, shorter hair; it just doesn't have that hippie undercurrent, and it doesn't have the same cultural associations that a West Coast crowd has— environmentalism, vegetarianism, the rest of the hippie causes. That's not to say I'm a vegetarian myself, because I'm not. But there's something about the West Coast that's retained a very powerful myth of that culture, Northern California in particular. So the Grateful Dead operate from a very strong base here, although I'd say there are probably more Deadheads in New York and even in places like Virginia or Pennsylvania, believe it or not." REGAN: "New Jersey... " BLAIR: "But the whole tenor of it is different." REGAN: "We can tell by the mail we get at Golden Road, subscriptions and such, that there are Deadhead enclaves in all sorts of places—Boulder, Colorado, or Eugene, Oregon—and it's interesting that there are these thousands of Americans that share an attitude that isn't defined, and it certainly isn't coming from the band in any kind of didactic way. You know, they aren't laying out principles for us to follow or anything. It's just a matter of . . .” BLAIR: "Kindred spirits, really." REGAN: "Yeah, and it's a form of bohemianism, in the same sense that the '20s in Paris were bohemian. Most of these folks—at least the wing I identify with—are intellectual, concerned about the earth, concerned about challenging music." BLAIR: "Of course, there's a party wing of Deadheads that just goes there to party and get high, which is fine too. It's not exclusive. As I'm sure you've read in a thousand articles, there are doctors, lawyers. Every profession goes to see the Dead, and I think that one of the most interesting things about it is this bizarre amalgam. We have three or four friends who are geologists; we also know doctors, lawyers, all of them people we've met at Grateful Dead shows, people we wouldn't have been exposed to otherwise." REGAN: "There's one guy we know who works as a geologist, with a specialty in solid-state metals—I mean, he's so far out there in geophysics you can't even imagine what he's doing, and he can sit there and talk to someone who makes bead earrings for a living. And if they're talking about the music they can have an honest exchange, a stimulating conversation." • • • Maybe you feel it, too—there's something in the autumn air. Cleansing winds of change are blowing through the Grateful Dead scene, stripping away ancient cobwebs and carrying in their currents the seeds of joyous rebirth. The past few months have tested us all and forced us, for the first time really, to come to grips with the mortality of the band. It has been a period of self-examination and introspection for many Deadheads; for others, the Dead's hiatus inspired them to reach outside the Deadhead community for new sources of magic and fun. It sometimes takes a cataclysmic event—like Garcia's near-death—to shake us off our treadmills. As blissful as the touring life at its best can be, it also exerts a physical and psychic toll: a lot of us are unhealthy and unequipped for dealing with a world outside the Dead. So this break from touring has offered a good opportunity to slow down for a moment and move out of the hurricane. Our bones patched, we can hit the road again with new energy and vitality. Blair and Regan started putting out the magazine as a quarterly, but then loosened up the schedule so it comes out approximately three times a year; it averages fifty or so pages. Invariably it has an exceptionally handsome glossy cover (featuring everything from old woodcuts to neopsychedelic visual rave-ups by artists who are associated with the band or whom Blair and Regan know through their day jobs). Inside, the magazine features a straight forward graphic layout, all black-and-white, and editorial copy that would be the envy of many publications with bigger staffs and budgets. Regan does all the copyediting, and does it extremely well. (In the course of spending many hours poring over issues, I found only one typo.) Although much of the writing is done by Blair, there are usually several guest articles as well as brief accounts of shows the band has played since the last issue, written by correspondents who live in the areas where the shows took place. Inside the cover there's an editorial by Blair, followed by a letters section that takes up several pages. After that we come to the meat of the format. The editorial well is jam-packed with feature articles on subjects you might have anticipated—descriptions of new Dead albums and videos, interviews with band members— as well as pieces that are more unexpected. For instance, Issue No. 15 (Fall '87) featured a book review by Dr. Roger Jackson on a translation of Rainer Maria Rilke's Duino Elegies. A bit far afield, you say? Not at all, really: the translation was done by Robert Hunter, who wrote the lyrics to many of the Dead's best-known songs. And in Issue No. 14, there's a long piece called "A Day in the Country with Driver, the Lady and Big Jer," by Ken Babbs—whom you may remember from The Electric Kool-aid Acid Test as Ken Kesey's staunch first lieutenant during the let's-turn-America-on-its-head Merry Prankster days. Babbs now lives in Oregon, and the article in question is an account of a visit Garcia paid him soon after recovering from a grave illness a year or so ago. Blair's style and eclectic interests serve as the editorial framework for this wide- ranging fare. For instance: "It all started out with the French and English slave traders. Long before Paul Revere and Valley Forge and the colonies shook off their chains, the greedy colonial powers sent their ships to Africa and brought back slaves to work the land and build a new empire so white people everywhere could take tea at three and fan themselves on the front porch. The largest concentration of slaves in the New World was in New Orleans, which was part of France's huge Louisiana Territory until the still-young United States forked over the big cash in 1803 and sent the French packing. The Battle of New Orleans in 1815 was the final blow to the recalcitrant French who'd remained to defend their evaporating empire, a breathtaking saga immortalized in Johnny Horton's 1959 hit single." Right up until those last few words, my guess is that you were wondering what any of this could possibly have to do with the Grateful Dead. (Those last words would be something of a giveaway since the Dead have often performed the Johnny Horton tune—"The Battle of New Orleans"—mentioned.) The paragraph ran as part of Blair's "Roots" column in Issue No. 10, which went on to a discussion of the song "Iko lko," which is also frequently performed by the band and comes out of the Mardi Gras purlieu of Old New Orleans. Indeed, the "Roots" column—containing as it does elucidations on the musical, historical, and sociological origins of the many songs that the band has covered—is not only fascinating and well-written but shows just how closely the magazine's main topic, the Grateful Dead, connects up with the wider world. "The average record buyer isn't gonna get that kind of information," Regan points out. "Because the only way you can get it is by going to the library, digging up all these obscure references about blues players and stuff, and going to places like Down Home Music and sifting through the bins—you know, preparing the information, tracking down the origin of a song. Okay, there's this version and this version. You learn about this other version from the liner notes on this record, and find out that there's this other one but it's out of print. So you go to the library again and maybe you find it there. Or maybe you don't, and you keep on looking. That kind of legwork is something that only scholars and journalists are up to. Having that kind of solid content in the magazine was always important to us, and a lot of the stuff in . . . a certain other fan-type magazine is just, 'Well, me and my brother went to the show and our car broke down along the way.' We have funny ambience stuff like that in our letters section, but we're not going to be that self-indulgent when it comes to the actual feature part of the magazine." In a given issue of Golden Road you'll also find a regular item billed as "Set Lists," which gives not just brief reviews of all the shows that have taken place since the last issue but complete lists of the songs that were played at each show. (As all true Deadheads know, the Dead hardly ever play the same set twice.) I mean,

Actually, there is (believe it or not) some other context in which you could glean this information: a large paperback book called DeadBase, published in each of the last two years, that undertakes to do nothing less than compile set lists for every single show the band puts on. A friend of mine, who refuses to be named but who will allow me to describe him as a Deadhead scholar, showed me a copy of the tome, which covers the 23-year life span of the Dead. It had been given to him gratis because he (like other Deadheads of a statistical bent all over the country) had informally provided John W. Scott, Mike Dolgushkin, and Stu Nixon, the book's compilers and publishers, with set lists and appearance information. Flipping through it, I came upon a set list for a show that took place at the Hippodrome, in San Diego, in October of 1968—a concert I happen to have attended. For many years I didn't even remember this concert (probably because of all the drug abuse I visited upon myself in those days). When the recollection finally burst upon my consciousness sometime in the late '70s, I had the image of a young Jerry Garcia in a Mexican poncho rallying his team with a cry of "Let's do it," brandishing his guitar, and kicking into the opening chords of "Good Morning Little Schoolgirl." Now, twenty years later, sure enough—there was "Good Morning Little Schoolgirl" right at the top of the list. My Deadhead scholar friend gave me a copy of a printout of one of the Conference's sessions, and what should the topic be but the newly published DeadBase? The book's publishers had invited Conference users to correct whatever mistakes may have cropped up in the first edition (a second edition has since been published, incorporating, no doubt, much of the information that came out during this conference). "Seems to me that I remember some funny goings on in Santa Barbara in June of 1978," a user identifying himself as H. Michael Brown says. "Bonnie Raitt and Warren Zevon were on the bill. Lots of Hells Angels, and vrrooooommming of cycles. The guy behind me had a stomach with three belly buttons. Really strange." A user calling himself Joe Attitude replies, "I remember that show. Warren exulted us on by calling us something like 'derelict '60s acid freaks' or something." To which one Dan Levy responds, "I don't remember Bonnie Raitt, but there was another act that included the singer who sang some of the songs on Steely Dan's album, Can't Buy a Thrill. Also Elvin Bishop." Someone with the moniker Joe Bad, Jr., jumps in with, "I think that was the time a motorcycle was playing along with 'Not Fade Away,' right? By the way, I interviewed Warren Zevon a couple of years ago and he apologized to the Deadheads for his behavior at that gig." And so it goes: computers hum deep into the night, as set lists are honed and annotated and reminiscences near and far are dusted off. All of which, I admit, leaves unanswered a very salient question: Why? BLAIR: "A lot of that has to do with the tape collectors, who like to have the set lists so that they can make a judgment about what shows they want to get tapes of. So if a particular show is described in the magazine as 'A typical set list of common songs performed not that great,' then the collector will probably pass on it. Or if it says some show featured a really great version of a particular song, then maybe he'll go for it." REGAN: "Or if it says, 'Out of this set of three shows, the Friday show was really terrific,' then the tape collectors might go after that one." BLAIR: "Beyond that, set lists give someone the vicarious thrill of following a tour from city to city, which cannot be underestimated as a thrilling activity. Touring is very exciting. We haven't done that much of it; only a week here or there—say Colorado for a week, Red Rocks and Telluride. Once we went to Eugene and Boise; that was really fun. You leave your job on a Friday afternoon, go up to Eugene, check into the Hilton, see the show, then drive to Boise for a show there. You're thrown into all these different worlds, and you have this traveling pack of people all going through the same thing, strangers in a strange land. 'Discover America,' you know? Because Deadheads travel a lot, they have this amazing geographic knowledge, by the way. I mean, you want to talk about geographic literacy in this country—well, the Deadheads can tell you that the Scope Theater is in Richmond, Virginia, or that the Fox Theater in St. Louis seats five thousand and it's in this part of town. They're a well-traveled group.” REGAN: "Really, there should be more Deadheads teaching high school. Anyway, we get a lot of letters from people in the heartland of America, people who are nowhere near shows. People in North Dakota, say." BLAIR: "Where the Dead never play, ever." REGAN: "They may drive to Chicago or someplace to see a show, but maybe they can't. Or they live in Arkansas—places that just aren't on the touring schedule. If they're young and free enough in their situation, they may get to go out and see a tour or something, but otherwise their only way of keeping up with the band is by reading about them and getting tapes to listen to. So when they get to read show reports and stuff, it helps them feel like they're not totally out of it. Basically, we're historians; we're chronicling this living history as it's unfolding, the way a newspaper would. We're letting people around the country know about the interesting things that have been happening. Here's where the band played…” BLAIR: "Here are the projects different people are working on…” REGAN: "Here's an interview with somebody in the band during the last month, so you get to know what Jerry, say, is thinking about these days. It gives people a little window into various aspects of the scene, including the problems that come up. If you've looked at the letters section in recent issues, you've seen that there have been a lot of problems in the scene lately about garbage and gate crashing and bad behavior among Deadheads, largely because the band's gotten so big in the last couple of years. There are a whole lot of people coming along now who aren't being taken by the hand by some experienced Deadhead, who says, 'Okay, we'll go to the show, we'll be cool, we'll hang out in front for a little bit, then we'll go in and get our seats.' It's more like someone hears them on the radio, they get a ticket to the show and say, 'Hey, yeah, Grateful Dead! I hear they're a big party band! Let's go, let's drink 45 beers, and trash the place.' They're not coming out of a mellow culture and they're not bringing that into the arena, so it's different. • • • Recently I was in my hometown visiting

sweet Marianna, who works at the local Fotomat. While she was busy, I had a notion to play my luck on a lottery ticket, since

there is a little store that sells them right next to the Fotomat. While Marianna

from the other direction was caught in my eyes, I figured I might as well try, might as

well try. (I play once in a blue moon.) Well, I had one Grateful tape in my car at the time—Boise, Idaho 9-2-83. So I played pick 4 9283 box and won $89 on a 50 cent ticket. That's a free pass to four Dead shows!

There really is some magic in those tapes. Toward the back of the magazine, there's another fascinating regular item called "Tape Traders," a free classifieds section for persons whose avocation is taping and collecting tapes of Dead shows. And if you think these are folks who have a few cassettes moldering in a drawer somewhere, think again: In case there's any confusion in your mind, what these people are talking about when they say "hrs" is total hours of recorded music. If you went to visit the person who wants the Universal Amphitheater shows and undertook to listen to all the recorded Dead shows he has in the hopper, you'd be there for several weeks without ever hearing the same note played the same way twice. BLAIR: "I think taping is the cornerstone of the Dead scene, because it provides a form of continuity for people to stay with the Dead even when they're not actually on the road. And the tapes are interesting for the same reasons that the shows themselves are interesting: they're all different, and each has its own story. As a phenomenon, it's obviously unique in the musical world. There's nothing comparable, especially in that the Dead don't only allow it to happen; they set up a special section at shows to actually facilitate its happening, where tapers can set up their equipment and even plug into the soundboard." REGAN: "Sometimes when people hear about it, people who aren't in the Deadhead scene, they think it all sounds very weird. Like this guy at work asked me, 'Well, what is this taping business?' And I told him, 'People give each other tapes, they trade tapes. They have a tape of a show, they make a dub of it for someone else, and then they give it to that person; and then the other person gives them a blank in return or trades another tape in return. No money is exchanged, and nobody has gained anything except the music.' And the guy looked at me and said, 'Why, that's so nice! It's so '60s!' I mean, whoever heard of this, of people doing something for somebody else for no profit? It's not a common thing, but it's certainly common in the Dead scene, and people don't think twice about it. I think there are a couple of scumbags on the East Coast who actually do sell tapes, but mostly it's just not done." BLAIR: "Usually, if someone tries to sell tapes, the word gets around and that person is ostracized. It's just not cool. Part of the reason the Dead allow it to happen is because it's supposed to be noncommercial. In general, people aren't taking these tapes and going down and printing up 3,000 bootleg records. Of course, there are Grateful Dead bootlegs, but it's very minor. It's not anything like Springsteen or Dylan or any of the traditional bootleg artists—just because there's no market for it, since you can get it for free." REGAN: "And tapes are a nice way for people to get together, especially people who live in nonDeadheady areas. We get a lot of letters from people saying, like, 'I moved to Orange County to take a job, and I didn't think there were going to be any Deadheads here. Then I saw an address in Tape Traders, and so I wrote to them; and now we go to shows together, I see this guy twice a week, and he's my best friend.' And that's really touching, to find out that something we did with our hands brought human beings together. Of course, we're just the middlemen between the Grateful Dead and those guys, but it's nice to have a hand in that kind of humanistic stuff." I have a theory about all this, and it goes as follows: When all the Prankster/Haight-Ashbury people were dropping LSD several times a week back during the '60s, the idea was that the acid high—which is characterized by a fierce influx of sensory, perceptual, and conceptual data—was the new reality that everyone was going to be living in permanently. Well, they all found out after a few years (at the most) that you simply can't go on indefinitely ingesting these powerful chemicals because things just get too weird. There ensued a period known as the early '70s during which post-ecstatic letdown was all but palpable. The hippie/acid thing was dead so now what? Meantime, the stage had already been set for a new way of life that would be characterized, once again, by a constant rushing about of information. Only this time the information would be on tapes and printed sheets, and in telephone lines and databases, instead of going off like cherry bombs right in the middle of your synapses. To an extent, what we're seeing in the Deadhead scene is the drug culture sublimated (and, in some instances, not so sublimated). If you take any piece of what seems to be trivial and inconsequential information and place it in a very tight frame, it will suddenly become fraught with stimulating import and significance. Mass together hundreds of thousands of such bits and you've got an ongoing charge that will carry you through your days (and have the added advantage of not turning your liver into a sponge or making you subject to psychotic episodes). Timothy Leary has been saying recently that computers are as addictive as heroin, but the fact is that information plain and simple is as addictive as anything you can think of. Need them tapes to feed that jones. But even though information can become its own reward, the entire brew is immeasurably enriched if it flows from a central locus that has a fascination of its own. I suppose this is why you're reading an article about The Golden Road and the WELL and the tapers instead of one about Bechtel Corp's employee newsletter and computer network and annual picnic. Still, one can't help but occasionally ponder the imponderable: Why the Grateful Dead? Why not Jefferson Airplane, or even Quicksilver Messenger Service? BLAIR: "Well, not to take a negative approach to the question, but Quicksilver could never write good original material. The Dead can. The Airplane was a great band, but they were too loud and they felt things too strongly and they burned too brightly and incandescently; and there were a lot of interpersonal things going on in the band. Also, they had this definite political undercurrent to what they did; the Dead never had that. The Dead say that while other bands wanted to effect change, they're interested in reflecting the change that's going on. Really, the Grateful Dead have more communication with their fans, and on more levels, than any other band in history. They have a hotline, for crying out loud." REGAN: "When Jerry was sick, people would call up and there were actual members of the band on the tape. Everyone was very frightened. A show was canceled, word got out that Jerry was sick, people didn't know what was going on, and they'd call the hotline and Phil Lesh, the bass player, would be on the tape saying, 'We want you to know that Jerry's feeling a lot better.' It was just this wonderful thing, and no band in history has ever done something like that before. It's pretty weird that the band has a hotline to begin with." BLAIR: "There's nothing to compare with the rapport they have with their audience. There's no other band where X percent of the audience knows who the sound man is, who the monitor mixer is on stage. There's nothing comparable; it's a different level of fandom." |