|

|

Of Speckle-Faced Rats and Supernovas Story By ROGER ANDERSON It’s a commonplace to say of poems that they live and breathe, but in the case of Michael McClure's work it seems almost literally true. His poems are like animals inhabiting the page, organic systems of spirit and substance. You can almost see (or hear) the blood flowing from line to line, feel the heart beating in each word.

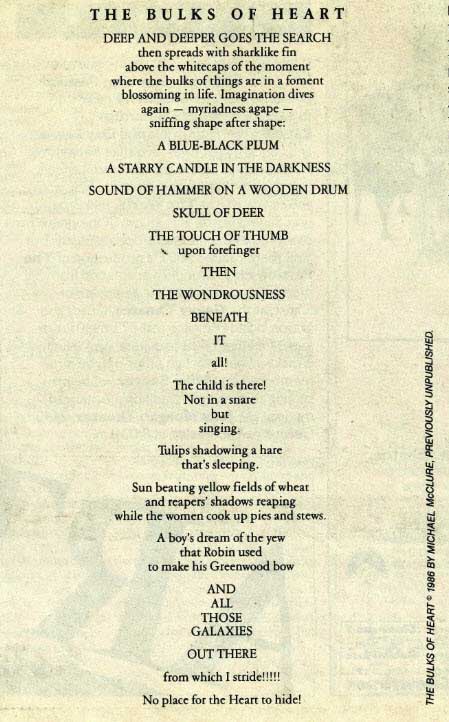

So when New Directions published McClure's Selected Poems this month, it wasn't simply that the first major retrospective of an important American poet had been issued — it was as though a family of strange animals or a cluster of exotic plants had been unloosed on the world. On every page, you are confronted with the imperative to perceive with all the senses the immediate, sensual, almost carnal glory of the universe. And the publication last December of McClure's Specks (Talonbooks) presented the poetry-reading public with a compendium of wisdom that is more than wisdom, systems of thought that begin and end in the body. Finally, word that McClure would be giving a reading at Black Oak Books was enough to convince anyone, let alone the present writer, that the moment had come to take a good look at the long and extraordinary career of this self-described "mammal patriot,” who has stood at the frontiers of American culture for over thirty years.

A few days before the Black Oak reading I paid McClure a visit. As I entered his Victorian flat in the Haight-Ashbury District, these lines from "Stanzas Composed in Turmoil" forced themselves out of my memory: "Hear / me tell you there / are fuschias here upon / the table in that vase / upon the tartan, mohair drape / of blue, green, white, red.” Lovely and memorable words, and I could see now that they were directly inspired by the poet's own habitat: fuschias bloomed in pots, mohair blankets hung across a banister; tiffany windowpanes, rattan and wooden chairs, a small woodstove, and a smell of incense filled the senses with the poem's life. McClure greeted me kindly and served up a cup of espresso as dark and strong and concentrated as one of his verses. Emboldened by his hospitality and by the black brew, I began the interview by remarking that his poetry shares with Allen Ginsberg's a debt to the visionary writings of William Blake. "Interestingly enough, the first time I met Allen was at a reception for W.H. Auden in 1954," he said, "and the first thing we talked about was Blake. I was immediately aware of how different our two Blakes were. Allen comes to Blake through the Old Testament, while I, on the other hand, originally came to Blake as a mystic atheist who had been reading Swedenborg. My Blake is the Blake of man's perceptions -- I was interested in liberating the fairies and elves inside me: while Allen at that time was interested in becoming a bardic saint. We were both very young men back then, a couple of kids talking about Blake at a party for W.H. Auden.” "When I was about five, I went from the intensely seasonal plains of Kansas, the core midwest, where summer softens the tar on the streets and where tornadoes blow, to Seattle and the rainforests of the Pacific Northwest,” he replied, “And I think that going from one extreme to the other climatically, and also the fact that I was moving to Washington State to live with my grandfather, who was a doctor and an amateur naturalist, was a very big experience. I wouldn't call it a conversion experience, although, taken as a whole, it could be described that way.” Regarding his core aesthetic, McClure said: "I was always interested in a sense of proportionlessness that I found in life and that echoed the proportionlessness I found in myself; that there is no scale or measure to spirit, and that all things are comprised of spirit, so that all notions of logic, measurement, counting — when you're dealing with things of the heart or things of the senses — are relatively meaningless. I mean, there's no difference between the size of the beating heart of a speckle-faced rat and the size of a supernova, essentially. A sense of proportion, of course, is terrific for building Golden Gate Bridges; and Golden Gate Bridges are then themselves things of the spirit and of beauty, so that proportionlessness enters through the side door. "Maybe it will be,” the poet said doubtfully, smiling. ”I'm not convinced that anyone will be there. But I like to do readings. It's important that my poetry is in books, but it's important also that people come to hear it. That way, it's not just words on a page; were all together as biological entities" The night of the reading, a furious storm descended on the Bay Area — turbulent seas falling from the sky in wave after wave. Nevertheless, the back room at Black Oak was jammed to the rafters, every folding chair occupied and SRO. Eschewing (even in such justifiable circumstances) the fashionably late arrival of many poets of comparable stature, McClure appeared only a moment or so after the scheduled eight p.m. starting time and picked his way through the crowd to the lectern — slender and graceful, moving like one of the many otters that populate his poems. After greeting the audience warmly, he opened the Selected Poems and launched right into “Antechamber,” a major poem from 1978. He read for about an hour, sweetly, moderately, lyrically, and the crowd hung on every word. This was not the fierce young poet who in the mid-‘60s read a section from Ghost Tantras (poems composed almost entirely in a nonsemantic "beast language") in a roaring voice to the lions in the San Francisco Zoo and caused them to roar back, but a gentle singer who had weathered the world's storms and was not so proud or fierce that he would neglect to address one poem especially to his wife — leaning toward her from the lectern, sending each word expressly to her ear. After the reading, well-wishers and admirers swarmed around him; I took up my umbrella and made my way outside. One mark of great art — whether a movie, a novel, or a book of poems — that it makes you see the world through the eyes of the artist, if only for a few precious moments. The rainy East Bay night was like one of McClure's poems: fluctuating, explosively alive, filled to overflowing with physical and spiritual vibrancy. I shouldered my way through it all, drove home, and fell to sleep like a hibernating animal. |