|

|

Story By ROGER ANDERSON In the first part of my work, Theophilus, I wrote of all that Jesus did and taught from the beginning until the day when, after giving instructions through the Holy Spirit to the apostles whom he had chosen, he was taken up to heaven. He showed himself to these men after his death, and gave ample proof that he was alive: over a period of forty days he appeared to them and taught them about the kingdom of God. While he was in their company he told them not to leave Jerusalem. "You must wait," he said, "for the promise made by my Father about which you have heard me speak: John, as you know, baptized with water but you will be baptized with the Holy Spirit, and within the next few days."

Let me begin by explaining why that first verse of the first chapter of Acts of the Apostles occurred to me as I was walking in the 6400 block of Imperial Avenue in Spring Valley's Encanto neighborhood. Along that stretch of Imperial, there's a line of ramshackle shops and storefronts: a wig store a transmission repair shop, a fraternal-order supply house (“We: The Brotherhood Connection"), a bar on whose front are painted gaudy depictions of men and women hoisting cool ones and from whose doorway the click of pool balls and the blare of jukebox mariachi issues, a baitand-tackle shop, another bar, the Alana Foundation ("Community Pride in Action"), and no fewer than six churches. The Acts text that I recalled is in the form of a modern translation, specifically, that given in the New English Bible. The NEB is a text favored by mainstream churches like the one I attend, the Episcopal Church, which, in recent years, has served as a kind of bridge between the sacramental ethos of Roman Catholicism and the conscience-driven practice of the Protestant sects. This means, however, that it is, in some ways, a church that is neither fish nor flesh. By outsiders, it is perhaps best known for its role in the early and later history of this country as the religion of choice among the ruling classes of the Northeast and South and for the comparative general affluence of its members - for its golf tournaments and wine auctions. But on this Thursday afternoon, I parked my car and walked along Imperial, noting the names and situations of the storefront churches that had caught my eye. At the corner of 65th and Imperial, was an extended, down-at-heels commercial structure housing no fewer than three churches: Joy Missionary Baptist, The Helping Hand Church of God in Christ, and Salem Baptist Church. Further down was Templo la Hermosa Pentecostal Asembleas de Dios and the Word of Faith Apostolic Church. Iglesia Apostolica de la Fe was actually contained within a building that seemed to have been constructed specifically for the purpose of worship services. I ambled along the street taking notes, drawing a few stares (there were not many white males in the vicinity), and trying the door of each church. Nothing seemed to be going on inside them; no one answered my knocks. I went back to my car and drove home, figuring I'd come back to Imperial Avenue on Sunday morning. So, when they were all together they asked him, "Lord, is this the time when you are to establish once again the sovereignty of Israel?" He answered, "It is not for you to know about dates or times, which the Father has set within his own control. But you will receive power when the Holy Spirit comes upon you; and you will bear witness for me in Jerusalem, and all over Judaea and Samaria, and away to the ends of the earth."

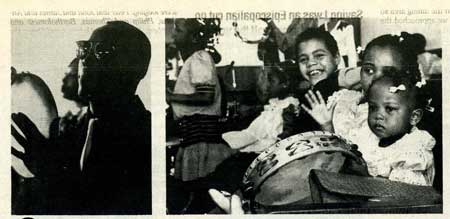

I told him I was a writer from a weekly newspaper and asked if I could come in to observe the services. He ushered me inside, asking my name. Going by the usual California code of (white, middle-class) informality, I provided him with my Christian moniker, Roger - the result being that over the next couple of days I was invariably referred to as Brother Rogers. Inside was a large room into which white-hot sunlight poured through a full array of streetside windows; there was an abundance of old pews upholstered in a sturdy red fabric, facing these a podium with a plain wood cross raised on its front, behind the podium more pews where church dignitaries could be seated, an organ, a piano, a drum kit. The faithful mob I had anticipated was nowhere to be seen; instead, a scattering of middle-aged and elderly black women and a few kids were seated around the space. Almost all the women wore immaculate white dresses and veiled hats. Elder Gray, the man to whom I had introduced myself, asked me to sit on the left side of the church for a Bible study class; I took a seat behind three women, who immediately turned and asked me to sit in front of them. The feeling that I was - uncustomarily - being deferred to on the basis of my gender made me a bit uneasy.

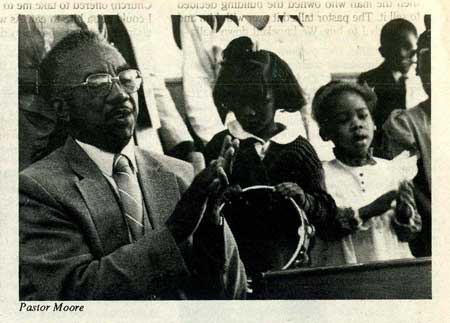

Mother Gloria Brunson, a plump, handsome woman in early middle-age rose before us and introduced the text for the day: Philippians 1:12-26, in which the Apostle Paul, imprisoned because of his beliefs, enjoins his flock to continue the good fight. Someone handed me a booklet entitled "Power for Living," which contained this and other texts, along with explications, comments, and illustrative contemporary anecdotes. Mother Brunson was an animated and thoughtful teacher. Elder Gray, too, pitched into the discussion with great energy. Everyone agreed Paul here was acknowledging that many of his followers since his incarceration had redoubled their efforts to preach the gospel - and that a few of them were doing so out of hope for ascendancy among their peers, or were vainly knocking their sconces together over doctrinal matters of small moment. Paul's point, as it was taken by Mother Brunson and the others, was that it matters not why the gospel is preached, so long as it's preached. This led to a discussion of how wrong it is to judge others' motives too quickly or without due humility. "I was out on the street one day and I saw a preacher smoking a cigarette outside his church." Elder Gray said, "and I couldn't help it; I figured in my mind that that man was no true preacher of the Lord's word. ’Course, I smoked for 20 years myself, but after I was saved I gave it up. Then later I heard that preacher preach - and he delivered the word of God so truly and so faithfully, I knew I'd gone beyond myself in judging him. Or look at it another way: I could get hit by a car tomorrow while unworthy thoughts are in my heart and go straight to hell, while that preacher might die repentant in the bosom of the Lord and go straight to heaven. So who am I condemn him for smoking a cigarette?" In the meantime, the children were clustered in various parts of the room getting instruction from the women. Eventually, a very tall, very powerfully built woman - the Sunday school superintendent - broke the session up by advancing to the front of the church, singing, "There's something on the outside working on the inside," and everyone joined in. The teachers presented their charges to demonstrate what they'd learned. As the children struggled with their gospel scenarios, I saw a bemused looking black man of about 60 and an imperious woman of about the same age walking along the sidewalk to the front door: the pastor, Elder Ozelle Moore, and his wife, Mother Moore, as it turned out. Pastor Moore took a seat behind the podium; Elder Gray sat next to him and brought him up to date on the morning's events, once or twice nodding in my direction. Then Elder Gray rose and addressed the congregation, which was growing in size by dribs and drabs, pursuing themes that had been brought up during Bible study. "One thing I've learned working at Big Bear," he said, "is that if people aren't set to hear the word, nothing you do will make them want to hear it. When the fellows I work with start telling dirty stories, why, I just go over to the Coke machine and have myself a Coke. And they may not be saved themselves, but they respect the fact that I belong to the Lord. Nowadays, when one of them uses a dirty word when I'm there, he'll come over later and apologize." His remarks were met by sundry spontaneous amens and praise the Lords and by Mother Moore - who had taken a seat in a pew behind me - rising every couple of moments to offer commentary. At one point, she managed somehow to work the theme around to a condemnation of makeup. I figured she must have meant this pointedly, since I could swear that some of the other women's faces weren't innocent of the stuff. As more people arrived, Pastor Moore got up a bit sleepily and took the podium. He made a few elliptical remarks about what had been said, then quoted a passage of scripture at some length; then he suddenly broke off and took a little piece of paper from his pocket, regarding it with a puzzled expression. It was a bill from the power company, he said, and it reflected a charge of nearly $400 for water for the previous month, as well as a "sewer fee" of more than $200. He spoke of having discussed the matter over the phone with a representative of the power company, who advised him there was probably a toilet leak somewhere in the building that had given rise to the exorbitant charge. Pastor Moore seemed understandably nonplussed by the whole thing. I kept expecting him to launch into an appeal for funds from the congregation, but the appeal never came. His remarks had the quality of thinking out loud, to no particular end. Then he changed subjects again. "Elder Gray tells me we have a visitor this morning," the pastor said, "a man from a newspaper. Brother Rogers? Won't you say a few words?" I noticed he was looking directly at me. Brother Rogers? Say a few words? I half rose from my seat and asked if I'd heard him correctly. Yes, I had. I got up and turned toward the congregation. The room was nearly full now, and I noticed a sprinkling of white men and women seated toward the back. Otherwise, it was a sea of black women in clean white, and well-suited black men with neatly kept pencil mustaches and lower-lip whiskers. "Urn, I want to thank you all for making me feel welcome,” I stammered. "I'm an Episcopalian myself, and I'm working on a story for a weekly newspaper.” I mentioned the name of the paper; and thanked them again. As I resumed my seat, I realized that the white congregants nodded knowingly at the name, which had caused not a flicker of recognition to pass across the black people's faces. A ten-minute break was declared, after which the main service was to begin. Everyone got up and milled around. I asked Elder Gray to introduce me to the pastor; we tracked him down out on the sidewalk. Hoping to break the ice, I commiserated with him on the power bill. The pastor drew the offending document from his pocket, and we both shook our heads over the craziness of it all. I prevailed upon Elder Moore to introduce me to the pastor of Salem Baptist. Inside, we found Pastor F. Marvin Young - a bald, intense-looking man. He seemed a bit nervous, perhaps at receiving a visit from his landlord right at the moment when Sunday service was scheduled to begin. He greeted me hurriedly and invited me to take a pew. Pastor Moore gave me his card and returned to his flock. The Salem Baptist space was drastically smaller than Helping Hand's - long and narrow, cluttered with religious bric-a-brac and a wedged-in piano that went unplayed during the service. In front of the piano, two black women sat facing the congregation, which numbered around fifteen. No sooner had I seated myself than one of the women, wearing a yellow dress and a veiled hat, broke into a groaning "Amazing Grace"; the other woman, who wore a floral print dress, joined in, and then the rest of the congregation. Yellow Dress gazed very, very intently toward the ceiling as though expecting the Holy Ghost to make a fiery descent; Floral Print rocked back and forth singing with her eyes closed. Almost invisible behind the piano, except for the top of his bald head, Pastor Young and an assistant sat giving pentecostal cry throughout the hymn. Meanwhile, organ syncopations percolated through the wall from Helping Hand, whose main service also was getting under way. The Salem liturgy consisted of spontaneous testimony from members of the congregation, interspersed with a cappella hymns. "When someone asks me if I've had a good night's sleep," one woman testified, "I tell 'em that God rocks me to sleep every night." Another hymn. People beat on tambourines. Cries of "Yes, Lord" become more ferocious, otherworldly. Yellow Dress got up and testified about her ulcers. More hymns, more tambourines, more cries. One of the ushers placed a woman, a late arrival, next to me; a moment later she spied a seat in another pew and moved there. The walls of the narrow room seemed to be drawing closer together.

Many of the storefront churches you see might be described as wildcat operations - small-p pentecostal sects with only the loosest ties (if any at all) to an overarching regional or national organization. Helping Hand Church, being part of the Church of God in Christ, is not among them. The COGIC was founded in 1895 by Bishop C.H. Mason, a former Baptist clergyman; the first services were held in an abandoned cotton mill in Mississippi. In 1907 Mason and a number of like-minded black Southern preachers formed the first COGIC General Assembly. Today, the national church (its headquarters is in Memphis) sanctions various ecclesiastical jurisdictions around the country, which in turn countenance church districts, each comprising a handful of local churches. Helping Hand is one of three local churches within the Unity District, which is a component of the second ecclesiastical jurisdiction (Southern California). Other women greeted this last news with cries of amen and praise the Lord. As an Episcopalian from a liberal background, I was thunderstruck. Where I come from, the notion of a wife not having to work is not even a consummation devoutly to be fantasized; it's a chimera, a vague memory from an earlier time - from a pre-feminist time, at that. I was beginning to understand that in the world of Imperial Avenue religion, the feminist movement might never have occurred; over the course of the afternoon, more and more evidence of this - tiny pieces of behavior - came to my attention. Once again, Pastor and Mrs. Moore arrived late, strolling up the hot sidewalk to the door, coming in, seating themselves just as the afternoon session began breaking up in the midst of song. People filtered out of the room and walked down to a small space at the end of the building that serves as the church's communal dining area, where a meal had been prepared to tide the flock over till the evening service. Inside the church, I cornered Mother Brunson, who sat with me and answered my questions about how she happened to be a member of Helping Hand. “As time went on, a few more people came in - but not many. There was plenty of work to do; we all did double, triple duty, because the work had to get done. For that first year, '78 and '79, we were a mission - Helping Hand Mission; after every service, we'd turn the chairs around, get out the table, and have a mission dinner. After a while, a number of kids came into the church, then a few more adults. We were paying $120 a month for the room. "In 1980, the Lord told the pastor it was time to move on. The pastor was walking along Imperial Avenue here one day and saw this place, which used to be a restaurant. He checked with the owner. The rent was high - five or six hundred dollars a month - but the Lord said to go on ahead. So we got our trustee board together and rented the place. The church began to grow, more and more people coming in, and then the man who owned the building decided to sell it. The pastor talked it over with him and we decided to buy. We knocked down walls - this used to be the kitchen. The Lord also blessed us by bringing us two other churches as tenants. That is, Salem Baptist was already here, and Joy Missionary Baptist came along by and by. We all celebrate together at a sunrise service every Easter. To hear what goes on here, you couldn't hardly tell that these other two churches are Baptist and that we're Church of God in Christ because all three sound like they're coming out of the same trend - you hear the organs, the drums, the people praising the Lord. "I work as an admissions clerk at City College, and the people I work with know about my church life; they know I'm saved, and they respect it. The Lord has given me favor with the people on my job. I love working there and I love the people. I don't have any problem discussing scriptures with the ladies on my job." Mother Brunson (as an original member of Helping Hand, she holds the title Mother of the Church) offered to take me to the dining area so I could get a bite to eat. As we approached the dining-room door, she stopped and waited for me to open it. I missed a couple of beats before picking up the cue. (Many, if not most, of the women I know would be at least perplexed if I were to go out of my way to open a door for them.) Once inside, Mother Brunson moved toward a table in the center of the room and seated herself; as I began to take a chair alongside her, not noticing that the table was occupied entirely by women and children, she enjoined me to go sit at the table where Pastor Moore was holding court with a few of the male congregants. “You should sit with the dignitaries," she said, laughing, plainly embarrassed by the faux pas I'd nearly committed. I did as she suggested, and the young pregnant woman - who, I now realized, was the daughter Mother Brunson had spoken of—brought me a plate loaded with breaded chicken wings and cake. As I ate, Pastor Moore asked me to tell him about the newspaper I worked for. As I tried to explain the nature of alternative weekly journalism, his look became increasingly opaque. I realized he'd probably never seen a copy of the paper I write for; after all, where was he going to come across one? At a record store? At a café? The other men drifted away, and my conversa- On the other hand, it was possible that the problem lay not with him but with me. Something about the idea of speaking in tongues has always frightened me, and it was seldom far from my mind that this is precisely what must sometimes go on inside Helping Hand. Also, I was raised in El Cajon during the '50s and '60s, when you could search from one end of the valley to the other without ever finding a black person. Pastor Moore's evident discomfort with my presence might well be a reflection of my own lack of ease. I found Pastor Moore back on Imperial Avenue taking a nap in his mobile home, which he had parked in front of the church earlier in the day. The engine was running to provide power for the air-conditioning unit, and he came sleepily to the door in response to my knock. He invited me inside and we sat down at a small table. I gave him my little premeditated speech, and as soon as the last words were out of my mouth, I knew that not one of them had made the least impression on him. The subsequent interview proved to be at least as halting as our earlier conversations. "I was a deacon at Israelite Church for 25 years. The Lord called me to the ministry in 1957, but I didn't want to do it. In 1959, the Lord told me to start Helping Hand Church, but I still didn't want to do it. In 1977 I gave up to the Lord, and in 1978 we started this church." Had he grown up in the Church of God in Christ? "I started out as a Baptist" How had he come to be a member of Church of God in Christ? “After I was grown I was exposed to Church of God in Christ, but the Lord didn't call my wife and me to holiness till 1953. Then we sold everything we owned in Mississippi and came to live in California?' Why didn't he want to be a preacher? Because it's hard? "No, the hard part was just that I didn't want to be no preacher." Why not? "I don't know. I just didn't want that." What had he done by trade before finally becoming a preacher? "I worked for the federal government as a civilian employee at the shipyards, at National Steel. I retired from there in 1985 with a small pension.” Now that he was at last a preacher, did he enjoy the work? Yes, it's very exciting - almost indescribable.” Did he see Helping Hand as having a particular ministry? "Yes. Helping Hand has a ministry of soul-saving, and it has a ministry of producing preachers and missionaries. Our missionaries do the Lord's work here on the streets and down in Mexico. It's on-the-job training - practical experience and teaching. They work downtown in Horton Plaza and other places. They help the needy, pass out food and clothing." Generally speaking, how did Helping Hand's members happen to become involved in the church? "Many of them were rank sinners and got their saving here." Did he believe that a small church like Helping Hand has something to offer that can't be found at larger, established churches? "We offer the fullness of the gospel of Jesus Christ. We believe that Christ does not share his glory with anyone else. We look upon him as the Son of God, we recognize his deity. We believe in the Baptism of the Holy Ghost; we believe in the Bible - that's our guide. We believe that the Holy Ghost is real." How does he envision Helping Hand ten years in the future? "I can just see a growth, but I don't know whether the Lord will let us stay here or move us out. Whatever He wants, we'll do." While the day of Pentecost was running its course they were all together in one place, when suddenly there came from the sky a noise like that of a strong driving wind, which filled the whole house where they were sitting. And there appeared to them tongues like flames of fire, dispersed among them and resting on each one. And they were all filled with the Holy Spirit and began to talk in other tongues, as the Spirit gave them power of utterance. There was a break in the singing and two women came forward to offer testimony. The first was in her 60s; she began speaking in a quiet, timid voice but before long worked herself up to a fever pitch and belted out a fusillade of praise and affirmation. The second, dressed like a chic office worker on her day off, was perhaps in her early 40s; she began by complaining of a cold in her throat, and she did in fact sound a bit hoarse; but within a few moments she was wailing away in grand, somewhat strident style. By the time the second woman had finished her testimony, the church was almost full, and more people were arriving every moment. Pastor and Mrs. Moore came in, Mother Brunson appeared, Mother Brunson's daughter showed up with her husband and children. A youngish white man in a suit, wearing a heavy mustache, his full head of dark hair brushed back, entered the church and sat next to Elder Gray in a pew behind the podium. One of the women congregants got up and scolded the late arrivals, admonishing them to show up on time the next evening, then introduced the white fellow as the master of ceremonies. Mother Brunson's daughter, looking more pregnant than ever, went up front and took her place at the organ. As the service evolved, it dawned on me that I was finally witnessing the lifeblood of Helping Hand worship, that after these days and hours of sparsely attended study groups, halting conversations with various people a frustrated desire on my part to be regarded as a sympathetic observer rather than merely an observer, I was finally seeing the Helping Hand people doing and feeling what it is that brings them to a storefront on a mean street every Sunday morning and, frequently, several times during the course of a week. The master of ceremonies began singing a hymn in a reedy Caucasian voice; the congregants joined in on the chorus; another verse, another chorus; tambourines appeared, were held high, smashed against the palms of hands. The hymn went on and on. It became very hot in the church; a woman went around distributing fans bearing the name of Greenwood Memorial Park and Mortuary and decorated with a florid design called "Autumn Cascade." Mother Brunson's daughter belied her gravid look by plopping her hands on the organ keyboard in perfect syncopation. I looked around; people had risen from their seats. The master of ceremonies brought the hymn to an end, and Mother Brunson's son-in-law went to the podium and began a prayer that rapidly turned into a song. Tambourines made a joyful noise. I looked around at the people I knew; Mother Brunson, Elder Gray, Pastor Young, all were standing and singing with their eyes closed, their arms splayed out before them and kneading the air as though hoping to embrace a Lover, looks of expectation and ecstasy on their faces. The white Episcopalian in me made a claim on my body and my mind: I felt suddenly not just out of place but as though I were peeping on strangers during a moment of profound intimacy. It seemed I had a choice: I could let myself go, throw out my arms, too, in anticipation of the Lover's embrace, or I could use the pandemonium as a cover and make good my escape. A moment later, I was out on Imperial Avenue unlocking my car. |