| Journalism

Was Ramona Real? How a Book Became More Than a Legend Was Ramona Real? How a Book Became More Than a Legend

Cut to Bob Dale - An off-camera chat with the bow-tied veteran of San Diego television Cut to Bob Dale - An off-camera chat with the bow-tied veteran of San Diego television

Salvation Row - An uneasy Episcopalian hears the word on Imperial Avenue Salvation Row - An uneasy Episcopalian hears the word on Imperial Avenue

Lester Bangs -The Hardback Lester Bangs -The Hardback

Dots on the Map - Heading East on Old Highway 80 Dots on the Map - Heading East on Old Highway 80

Silents Were Golden - Why early filmmakers zoomed in on San Diego Silents Were Golden - Why early filmmakers zoomed in on San Diego

Where Wild Things Were- Something is lost when something is built Where Wild Things Were- Something is lost when something is built

One for the Zipper- The quintessential carnival ride must bring chaos to the calm center of the soul One for the Zipper- The quintessential carnival ride must bring chaos to the calm center of the soul

Deadhead Redux - No one knows for sure why Grateful Dead fans have such a drive to communicate with each other but they do-and they’ve turned Blair Jackson and Regan McMahon’s “The Golden Road” into the most successful fanzine in the history of the form. Deadhead Redux - No one knows for sure why Grateful Dead fans have such a drive to communicate with each other but they do-and they’ve turned Blair Jackson and Regan McMahon’s “The Golden Road” into the most successful fanzine in the history of the form.

The Last Anniversary - An Altamont Memoir The Last Anniversary - An Altamont Memoir

Desolation Row -The lonesome cry of Jack Kerouac Desolation Row -The lonesome cry of Jack Kerouac

Faster Than a Speeding Mythos: Superman at 50 - Superman at 50: The Persistence of a Legend Faster Than a Speeding Mythos: Superman at 50 - Superman at 50: The Persistence of a Legend

When Art is No Object -The Eloquent Object - At the Oakland Museum, Great Hall, through May 15. When Art is No Object -The Eloquent Object - At the Oakland Museum, Great Hall, through May 15.

“He Wasn’t Dying to Live in L.A.” - Intrepid Journalist’s Last Dispatch Before His Collapse “He Wasn’t Dying to Live in L.A.” - Intrepid Journalist’s Last Dispatch Before His Collapse

Search for Honesty in Post-war Life - Plenty Search for Honesty in Post-war Life - Plenty

Armageddon Averted: Where Will You be on August 16. 1987? - Inside Art Goes to the Frontiers of the Mind Armageddon Averted: Where Will You be on August 16. 1987? - Inside Art Goes to the Frontiers of the Mind

Of Speckle-Faced Rats and Supernovas - Michael McClure Of Speckle-Faced Rats and Supernovas - Michael McClure

George Coates - The Physics of Performance and the Art of Iceskating George Coates - The Physics of Performance and the Art of Iceskating

No Escape from the SOUNDHOUSE - Maryanne Amacher No Escape from the SOUNDHOUSE - Maryanne Amacher

A Pynchon's Time A Pynchon's Time

Grants - State of Art/Art of the State Grants - State of Art/Art of the State

Poetry from Outside the Pale - Allen Ginsberg Poetry from Outside the Pale - Allen Ginsberg

Once Upon a Time - In Berkeley Once Upon a Time - In Berkeley

The poet from Turtle Island - Gary Snyder The poet from Turtle Island - Gary Snyder

Noh Quarter

Joyce Jenkins and the Language Troubles Joyce Jenkins and the Language Troubles

Philip Whalen Philip Whalen

|

|

The Last Anniversary-An Altamont Memoir

"We want to set an example for the rest of America about how people can behave in large gatherings."—Mick Jagger, lead singer of the Rolling Stones, before the Altamont concert

"Nobody kicks my motorcycle."—Sonny Barger, president of the Hells Angels, after the Altamont concert

Story By ROGER ANDERSON

December 8,1989

So there I was, stranded in the middle of a couple of hundred thousand people in a parched field near Livermore; I hadn't been able to go to the bathroom or get anything to eat or drink for several hours, my brain had been fractured by LSD, and I couldn't keep my eyes off the swarthy fat guy dancing naked twenty or thirty feet away in the midst of this all-inclusive human environment of longhaired freaks that stretched from horizon to horizon.

Fat, drunk, naked, with a black pencil mustache and neatly trimmed short hair —I couldn't help it, the fellow didn't seem to belong here. He looked like a sadistic guard in a Turkish prison. Yet here he was; he had traveled from afar just like the rest of us to party down with the Rolling Stones at this free concert, got sandwiched into the human environment like everyone else, got drunk, got out of his clothes, and now he was dancing like there was no tomorrow. Since the people in his immediate vicinity—jammed in cheek by jowl as they already were—had no desire to run afoul of his flailing limbs and gut, he had been somewhat desperately afforded plenty of room to maneuver.

And now, what was this? A much smaller fellow, also swarthy, also drunk, also naked, but not fat at least, had appeared out of the thick of things and was doing a feverish fandango right next to the other guy. The original naked dancer, upon realizing that his space had been penetrated, or else out of sheer unthinking volcanic energy, hauled off and punched the new arrival, who recoiled as though attached to an elastic cord and disappeared into the crowd.

"Christ," I muttered, rubbing my forehead. "Where the fuck did these people come from?"

"What people?" This was my friend Jim, who hadn't been paying attention.

"All these people," I said a bit unsteadily.

"The real question"—this from my other friend, Lester—" is what the fuck are we doing here?"

Good question, but entirely rhetorical. The three of us knew all too well why we were there: our regard for the Rolling Stones was close to idolatry. Still, it was amazing to realize that late the previous night we'd been five hundred miles to the south, minding our own business at my parents' house in El Cajon, decorously imbibing from a bottle of Jack Daniels and listening to the radio in my bedroom, keeping it low so as not to wake up the folks.

"We're getting word that the free Rolling Stones concert planned for San Francisco is on," the DJ had said. "The site is the Altamont Speedway some distance outside of the city, near a place called Livermore, and the time is tomorrow—December 6, 1969, a day that may live in infamy. That's right, folks: if you missed the Stones when they were in town a few weeks ago, now you can see them for free. All you gotta do is get up there. We're also hearing that all the big San Francisco bands—the Jefferson Airplane, Santana, the Grateful Dead—will play as well. Thousands of people are said to be arriving at the speedway already."

"Shit, man," Lester said, reaching for the bottle, "let's go."

"I'll drive," Jim put in.

And I would supply the car. I wrote a misleading note to my parents and we piled into my slightly battered blue '66 Falcon. We stopped. at a gas station for a map, at a friend's house to scrounge a joint, and off we went.

Lester had recently begun writing freelance for a fledgling but already influential newsprint rag called Rolling Stone. Right now, he was drunk as a skunk. "Hey, man, this is gonna be fucking great. Know what? Just a couple days ago I sent a review of Let It Bleed to my editor." (Contrary to dollar-wise '70s and '80s practice, the Stones had released a new album not prior to but in the middle of their tour.)

"They assigned you Let It Bleed?"

"No, I just wrote the review and sent it off. Maybe they'll print it. And maybe Rolling Stone'll have a party for the band after the concert, and maybe we'll get to go, and maybe they'll introduce us to Mick and Keith, you know, like, 'This is Lester, he's the guy who's reviewing your new album.' "

"And maybe we'll all get to ball Marianne Faithfull," Jim said.

Before long, Lester fell into an alcoholic stupor in the back seat. We were rolling down the north side of the Grapevine grade; it was already two or three in the morning. I lit the joint, took a hit, and offered it to Jim.

"Shouldn't we save some of this for Lester?"

"Didn't think of that," I said. "Lester, hey Lester! Want some of this?" Nothing but sopping wet snores from the back seat. "Guess he's not interested." I took another hit. Just then a red CHP light burst into flame behind us and to our left. A patrol car was maneuvering us to the shoulder. "Oh, shit," Jim said.

My window was already open a crack, so I shoved the joint through it. By the time we came to a stop it was lying on the ground two or three hundred yards behind us. The highway patrolman exited his vehicle, which he'd parked to our rear, and came up to Jim's window.

"Hey, chief," the cop said. "Everything okay in there? The car was weaving."

"Everything's just fine, officer," Jim replied politely.

The patrolman peered at his eyes. "Been doing any drinking tonight?"

I was starting to feel a little worried about the Jack Daniels bottle in the back seat when Lester came awake, spluttering. "Huh? Hey, what the fuck is this?"

"It's okay, Lester," I said soothingly. "The officer is just asking Jim a couple of questions."

This enraged Lester. "What is this, fucking Nazi Germany? Hey, pal, we're just on our way to catch some music; anything wrong with that?"

The officer was apparently put off balance by the torrent of vituperative indignation Lester proceeded to vent. A moment later we could hear the callbox squawking from the patrol car, something about a serious accident.

"Okay," he said. "You all go on. Only I don't think this man"—he pointed at Jim —"should be driving."

"Fine," Lester retorted, climbing out of the back seat. "Jim, move over. I'll drive."

We shifted, the patrolman sped away, Lester put the car in gear and we continued down the Grapevine veering wildly from one lane to the next. At the first exit Lester pulled over and got out. "One of you guys better take over. I don't think I'm up for this," he said blearily. He got into the back seat and took a pull from the bottle as Jim powered us back onto the freeway. "Say, where's that joint?"

By the time we arrived in the Livermore area, clear December daylight was pouring over the fields and hills. Automobiles were ranged in long haphazard rows hither and yon; young people swarmed across fields to coagulate around a makeshift bandstand that had been set up outside the speedway. There were already more people present than we had ever before seen in one place, yet we had no idea what was to come—no idea that we were looking at a regular hippie concentration camp in the making. (In those days, many people who took drugs and listened to a lot of rock 'n' roll firmly believed that the day was approaching when we would all be herded into detention centers on suspicion of mopery and dopery. No one, though, predicted that we would go voluntarily.) Thousands of freaks were arriving every minute.

Here was something nice: an entire avenue of drug dealers, a line of guys standing on a hillside hawking their wares.

"Great, maybe we can get some speed," I said.

No luck; nothing but psychedelics and reds—lots of reds. I wasn't partial to reds, so I bought some LSD for two dollars and swallowed it dry. Lots of other people were buying the reds.

We got as close to the bandstand as we could. At this point you could still see patches of ground, still make your way from one place to the next without too much hassle. But within an hour or so we looked up to find ourselves completely hemmed in: to move as much as ten yards in any direction would be a major undertaking.

"Did we bring any food, anything to drink?" Lester said. The Jack Daniels was long gone.

Jim and I looked at him. "Shit," I said. "You know what? We left the food in the car."

"Funny guy. That's another thing. Do you have any idea where the car is?"

"No," I said.

"Sure," Jim said. He peered off in the distance. "It's over there, at the juncture of those two roads. I think."

"Look, there's Tim Leary," Lester said.

Sure enough, there was the guru of LSD himself, suffering himself to be led through the walls of people by a young boy. He looked very old and drawn.

We were hemmed in there for a goddamn long time before anything in the way of music took place—hours during which untold thousands of new people flooded in and longhaired technicians eternally tinkered with the piles of speakers and cords on the stage and in the rickety scaffoldings. In those days, the extremely complex technical problems involved in sequentially wiring and unwiring equipment belonging to several bands performing on the same bill hadn't even begun to be solved. What you commonly expected was to spend hours baking in the sun between sets while the matter was dealt with by professional acid heads who kept dropping things, and for the concert to conclude long after the scheduled time. Here at Altamont, the problem was exacerbated by the fact that no one knew what was going on—the venue had been selected, after abortive consideration of Golden Gate Park and Sears Point Raceway, at just about the last possible minute, and the logistics involved were horrendous. Equipment was being trucked and choppered in from San Francisco by people who had never heard of the Altamont Speedway, or even of Livermore. When it arrived, there were those unspeakable hordes of disoriented freaks to reckon with.

"Have you noticed that there's a lot of Hells Angels here?" Lester said.

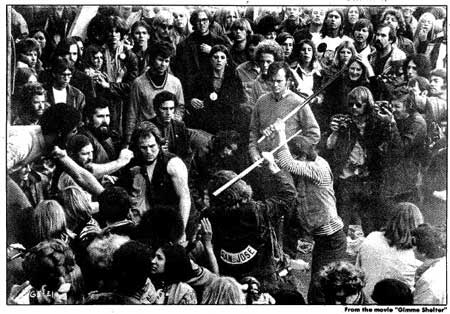

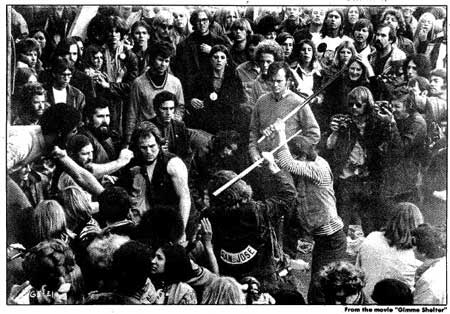

We had indeed. They were impossible to miss: big burly guys in Angels colors, many of them wearing repellant headpieces fashioned from the bodies of dead animals. Over here, a Hells Angels bus was parked and Angels and their "old ladies" sat on top of it getting drunk. (Hells Angels in a bus?) To our amazement, we eventually learned—via announcements that issued from the stage concerning the need to preserve order—that the Angels were in fact semi-officially present as what was later to be known as "event security." Many of them were carrying sawed-off pool cues.

This was not quite—not quite—as lunatic as it sounded. Although the Angels traditionally expressed nothing but hostility and contempt toward middle-class longhair peacenik kids on drugs, and although peacenik kids on drugs felt nothing but fear and trepidation at the sight of working-class swastika-wearing hoodlums on drugs and giant Harleys, the counterculture paterfamilias poet Allen Ginsberg some years earlier had effected a kind of rapprochement between the two camps by hooking the Angels up with Ken Kesey's acid-flashing band of Merry Pranksters, with whom the Grateful Dead were closely associated. The rapprochement seemed to work okay, and Angels became regular fixtures in the Prankster/Dead scene. This very association, we learned later, led to the Angels' semi-official presence here. Still, the situation seemed guaranteed to put the whole uneasy biker/freak alliance righteously to the test. (When the Dead, upon arrival at the speedway by helicopter late in the afternoon, heard what the Angels were up to, they judiciously elected to forego their set.)

The bands other than the Stones who were scheduled to play were the Flying Burrito Brothers (featuring former members of the Byrds), Jefferson Airplane, the Grateful Dead, Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young, and Santana. The Burritos were on first, and even then violence boiled up from the crowd and almost spilled onto the stage. It was impossible to discern its cause; all you could see was a spasm of people, an upthrusting of limbs, the flash of biker colors, pool cues swinging through the sunlight, people scrambling desperately and a bit uselessly to get out of the way. The disorderliness was heightened by the fact that no effective perimeter had been established around the stage; the audience was constantly, rather frantically being enjoined by the concert organizers to keep back. But it was hard to keep back with the press of thousands of shoehorned druggies pushing at you from behind like an insensate rip tide; again and again the demarcation between crowd and stage was erased and the event's center of gravity obliterated. This always seemed to signal that "anything goes"—the colors and the pool cues would flash, and the sickening thunk of hard-tipped wood against bone and skin would communicate itself through the crowd.

"Please, people, stop hurting each other," one of the Burritos called plaintively between tunes. "You don't have to."

Later: "We need a doctor. If there's a doctor present, please go to the area under the left scaffolding, please."

"Wonderful," Jim said.

Just then a scrawny, toothless Hells Angel came crawling through the mass of humanity behind us and clawed his way toward the stage with an insane look in his eye. We did everything in our power to give him a wide berth. A moment later, thank God, the crowd had swallowed him up.

Soon after that, a young guy and a young girl came shoving their way along. No one felt inclined to let them through. "Please, please, someone's hurt back there, he fell down and cracked his head open, we have to get a doctor," the boy pleaded. The crowd parted. CSN&Y happened to be on stage finishing "Down by the River," more fights were going on, and David Crosby was saying: "Let's try to be brothers and sisters to each other, now, come on!"

"Someone needs a doctor back there, asshole!" Lester shouted. He couldn't abide the band in any case.

Crosby: "Brothers and sisters . . .

" Lester: "DOCTOR!"

He had taken the young guy's tale to heart. We realized much later that the couple had concocted the story in order to force a path through the crowd: there they were, up close to the stage, bopping like they didn't have a care in the world.

The concert brought one fact home once and for all: alcohol had finally and truly arrived in the counterculture as an acceptable drug. For a very long time, it hadn't been. One of the big rationales behind using dope in the first place was that alcohol was such a miserable excuse for a high, miserable and unhealthy. Well into the first months of 1969, going down to the liquor store for a six-pack or some wine or a bottle of hard stuff was definitely a bottom-of-the-barrel proposition, something you did—somewhat shamefacedly—when you couldn't get any real drugs.

Getting real drugs, though, was a problem by late 1969. After taking office earlier in the year, President Richard Nixon had given his blessing to a program known as Operation Intercept, whereby every single car crossing the international border from Mexico was raked over the coals by customs inspectors—the idea being to cut down on the drugs being smuggled into the country. (The idea also was to discourage American tourists from visiting Mexico, thereby putting heavy economic pressure on the Mexican government to do its fair share in combating the spectre of rampant narcotics addiction.) Nixon's nefarious ploy was working. Drugs like pot and speed were hard to come by, sometimes very hard. (For some reason you still saw plenty of reds. And, of course, no border campaign could have any effect on the availability of psychedelics, which were manufactured and distributed domestically. But by 1969 most people were starting to grow a little bored with LSD and mescaline. Really, where did getting in tune with the universe leave you? Right back in the same tumbledown rented room with a sink full of dirty dishes and an urge to get numb.)

Meantime, the counterculture zeitgeist definitely had shifted away from censuring alcohol use to positively glorying in it. No rock festival was complete unless untold gallons of cheap wine were consumed. The winemakers, no dummies, spotted the trend and quickly supplied the hippie market with bottled potables like Annie Greensprings, perfect for sluicing down your throat while listening to a bunch of wasted longhairs croak about revolution and free love. In 1970, Rolling Stone would give alcohol its Drug of the Year award.

Reds were popular too. Brand name Seconal: pure downers, sleeping pills. In El Cajon half the people you knew—the same people who used to smoke grass and talk about how the Beatles were ushering in the kingdom of God on Earth —were constantly eating them or shooting them up and then putting their hands through shoestore windows or burning down a garage or showing up on your doorstep covered with mud. Reds made some people not just clumsy and stupid but downright mean and surly.

You didn't need a doctor to tell you that mixing alcohol with Seconal was about the worst possible thing you could do—everybody knew it was bad medicine. But hey, it's a party! Altamont was a major party, and a large and highly visible proportion of the people attending the party were drinking wine and eating reds thirteen to the dozen.

Things really started going out of control when the Jefferson Airplane mounted the stage, shoving their way through an encrustation of Angels and assorted drug losers, and slammed into "The Other Side of This Life." They were soaring along in the best airborne acid-rock style when a surge of random violence swept onto the stage and the song ground to a squealing halt.

"Easy, easy," Grace Slick cautioned. "It's getting kinda weird up here." Even as she spoke, another spasm of violence tore across the bandstand like a bad wind. A moment later Paul Kantner was at the microphone.

"I'd like to mention that the Hells Angels just hit Marty Balin in the face and knocked him out for a while," he informed the crowd. "I'd like to thank you for that."

Like to thank us? What the fuck did we have to do with it?

One of the Angels grabbed the other mike and faced Paul. "Hey, man, let me tell you what's happening here," he said angrily.

"I'm not talking to you, man," Paul said coolly. "I'm telling the people what happened to my lead singer, man."

"You're what's happening here, man," the Angel went on. Just then one of the stage crew killed the juice to his mike, and he stormed off the stage in disgust.

The Airplane tried to reconstruct their set. Marty was up and around and looking fine. "People should keep their bodies off of other people unless they intend love," Grace advised over a guitar vamp. "You need people like the Angels to keep people in line, but the Angels shouldn't bust people in the head. Let's not keep on fucking up!"

"We need the Angels?" Lester muttered. "That's a leap of faith if there ever was one."

"Besides," Jim said, "we're not the ones who are fucking up. Are we?"

It was around then that the naked fat guy came alone to gross everyone out with his dancing dugs. I was peaking, and it was only the horrified stares of other people that convinced me the guy wasn't a private figment of my imagination. Finally the strange tidal pull of the crowd—everyone was incessantly being pulled around the area in a slow-mo swirl, and our own position relative to the stage was constantly changing—put the naked dancer in the proximity of a contingent of Angels. The Angels took one good look at this guy, and it was as if someone had tossed a hand grenade; an explosion of violence ensued, the fat guy disappeared from view, and I thought I saw a couple of Angels looking down at the ground as though preparing to administer a coup de grace to a fallen adversary.

"I think they're snuffing that guy," I said.

"What's that?" Lester said.

"Over there, I think those Angels are gonna snuff the fat guy."

I was wrong, as it turned out. The killing wouldn't begin until later.

In the summer of 1969, when the Rolling Stones announced that they were going to tour the United States, it was one of the biggest deals to come along in hippieland in a good long while. As rock scribes and other pundits never tired of pointing out, "the Big Three stopped touring in 1966." The "Big Three" were the Beatles, Bob Dylan, and the Rolling Stones—the most glorious names in rock music. Although the counterculture thing had been brewing and fermenting since '64 or '65 in places like the Bay Area, it hadn't swept the rest of the country until well into 1967, and yet Dylan, the Beatles, and the Stones hadn't been seen performing in public since before that halcyon year. Our great gods had vanished from view even before their work on earth had righteously gotten underway. Before the stunning announcement of the Stones tour, all freaks believed in their heart of hearts that these gods would never again be seen disporting themselves in the flesh. Dylan, who had completely checked out of the public's ken in '67, seemed especially like a hero who had ascended on high, never again to commune with mortals. If you had told one of his fans then that the man would end up making hundreds of concert appearances during the '70s and '80s, you probably would have been answered with a pitying stare.

But along with all the hosannas and alleluias that attended the news that the Stones would once again be present among us, there were a few second thoughts. After all, were the Stones really all that relevant anymore? "Satisfaction" might be one of the greatest songs of all time, but it hailed from an era that was only slightly less embarrassing than the era of "Louie Louie" (a song universally disdained by late-'60s freaks, who generally believed that rock 'n' roll was an "art form"). Bands like the Airplane and the Dead breathed psychedelia as their natural element: when the Stones put out Their Satanic Majesties Request, in '67, the breathing was decidedly labored. Also, the band seemed kinda old: Mick was 26, Keith was 25, God knew how old Charlie Watts and Bill Wyman were, and the addition of the 20-year-old Mick Taylor after Brian Jones' ouster and subsequent death seemed a conscious if not outright cynical move to attract a younger audience. (Members of the Airplane and the Dead were actually older than Mick and Keith, but since those bands had only been in the public eye a couple of years they seemed younger.)

On the other hand, the Stones made a strong claim on the attention of America with the summer release of the single "Honky Tonk Women." A huge hit, it presaged a new legitimacy for unabashed country influences, one of the emerging keynotes of '70s music; with Charlie's hardhitting cowbell and Keith's raucous, freeze-dried riffology, it also rocked your bones down.

By today's standards—indeed by the standards of any Stones tour that took place subsequent to '69—this one was an amazingly small-gauge affair. The Stones went from city to city with a load of speakers that you would expect any successful bar band to possess today. They stayed in Holiday Inns. Later, it was reported that they'd each taken home a paycheck on the order of a couple of hundred thousand dollars. Their concerts were sold out, but there were no two-or three-day stands in football stadiums. At the Sports Arena in San Diego, the best seats in the house cost nine bucks.

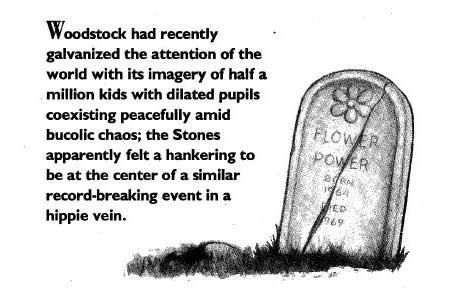

Of course, nine bucks was a lot of money in those days, and, in fact, the Stones came in for a lot of criticism in both the straight and countercultural press for charging so much. All through the tour, Mick was saying at press conferences that the band would make it up to people by holding a free concert at the end of the tour. That was one of the reasons for Altamont. The bigger reason, of course, was that Woodstock had recently galvanized the attention of the world with its imagery of half a million kids with dilated pupils coexisting peacefully amid bucolic chaos; the Stones apparently felt a hankering to be at the center of a similar record-breaking event in a hippie vein.

When the concert was finally announced, no one thought to ask how people in Denver, say, who hadn't been able to afford a concert ticket were going to be benefited by a free concert held in Northern California. As it turned out, thousands of people did come to the Altamont Speedway from as far away as Denver, New York, and much farther. And here they were now, in the cold December darkness, huddled in a huge mass, hungry and thirsty and scared, watching the Hells Angels slowly cut a path through the crowd with their Harleys so the Rolling Stones could make their way to the bandstand and preside over the crowning event of the glorious 1960s.

Oh, babies. Everybody just be cool now." Mick was speaking into the microphone as the other guys plugged in their equipment. He seemed slightly self-conscious in his cape and tights. "Just be cool." All around him longhaired humanity teemed; a naive observer might not have been able to tell that the band was supposed to be the focus of what was going on—the crowd incessantly spilled onto the stage, bikers paraded back and forth, gasping dogs trotted between rock-star legs.

There was no doubt about it, the Stones were nervous. They had every reason to be. Mick, whom no one ever accused of being unintelligent, must surely have known that by coming on stage he was plunking himself down on a burning hot seat. Anything could happen now. The Kennedys had been assassinated under far less outwardly threatening circumstances.

The band launched into "Jumping Jack Flash," then continued on with their usual set. When they reached "Sympathy for the Devil," I found myself waiting eagerly for the line "And I lay traps for troubadours who get killed before they reach Bombay," a string of incomprehensible verbiage I'd always found thrilling and fate-drenched. By the time those lyrics came around the shit was hitting the fan. Several fights were going on in the immediate vicinity of the stage; people were tumbling about like breaking waves as the pool cues described their appalling trajectories. Finally, when some struggling bodies landed right in the midst of the band, the song ground to a halt—except for Keith, who kept playing ferociously.

"Keith, Keith, will you cool it?" This was Mick. "I'm going to try and stop it."

Good luck. Keith cooled it and Mick pleaded with the crowd. "Now people, brothers and sisters, e-very-body just-a cool out! Everybody be cool, now!"

Everybody cooled out a smidgen and the band went back into the song. A verse or two later violence broke out again and the band stopped.

"Who's fighting, and what for?" Mick asked the crowd with desperate reasonableness. "Who's fighting, and what for? Why are we fighting? Why are we fighting?" Keith, less given to rhetoric, grabbed the other mike: "Either those cats cool it, man," he barked, pointing at some Angels, "or we don't play."

Somehow a biker got in front of a mike and sounded off in the manner of a frustrated teacher herding noisy fifth-graders through a field trip: "Hey, you people all wanna go home or what?"

"I can't do any more than ask you to keep it together," Mick again, sounding the conciliatory note. "If we're all one, let's show we're all one!" In a soothing manner (remember, people were in the habit of saying this guy was Lucifer incarnate) he helpfully directed medical attention to go here, there, over here, in a tone suggesting that the worst was over.

It wasn't, of course. But one thing you had to say for the Stones—and I continue to respect them for it to this day, despite the fact that they've turned into boring old money-grubbers--they rose to the occasion performance-wise. They didn't fold, they didn't hesitate; they blasted out their old and new tunes with fierce conviction. They took chances: as though trying to distract a bunch of fractious children with glittering new baubles, they played two songs no one had ever heard before, "Brown Sugar," which wouldn't hit vinyl and the airwaves for over a year, and something apparently called "Spend a Little Gold with Me," a goodnatured, lazy-tempoed throwaway that no one ever heard again. At some point Mick had the rather brilliant idea of telling everyone to sit down-not that easy a thing to do. But the sitting posture did seem to make everyone a bit more serene and less prone to get sucked into weird group vortexes. But when the dulcet strains of that misogynist classic, "Under My Thumb," began coiling through the night, some bad energy got released once and for all.

Thunk. Broil. Crush. Spill. Burst. Torrents of confusion. The band stopped playing.

Keith grabbed the mike again. "We're splitting if people don't stop beating on people, man."

The song resumed somehow. "I pray that it's all right," Mick crooned, changing the lyrics slightly. Did he know that a man had just pulled a gun a few feet from the stage? Did he know that the gunman had then been knifed to death by a Hells Angel? Probably not.

We didn't know it either. There were a lot of things we didn't know until long after the band had left the stage and we had groped our way in a daze through the human flood back to my car (it was right where Jim thought it was) and arrived in Berkeley to spend the night at the house of one of Lester's Rolling Stones colleagues. The TV news was full of Altamont. The dead man's name was Meredith Hunter; he was black; an investigation into his death was already underway. Meanwhile, there was a report that two people had been crushed to death after the concert when a car inadvertently drove over the sleeping bags they were lying in.

We were passing a gallon of wine around the living room; Lester was on the couch, snoring. "Wasn't us, was it?" I said.

"Wasn't us what?" Jim said.

"Wasn't us who ran over those people, was it?

"Very funny," Jim said. He took another drink of wine. "No, I don't think it was us."

back to top

|