| Journalism

Was Ramona Real? How a Book Became More Than a Legend Was Ramona Real? How a Book Became More Than a Legend

Cut to Bob Dale - An off-camera chat with the bow-tied veteran of San Diego television Cut to Bob Dale - An off-camera chat with the bow-tied veteran of San Diego television

Salvation Row - An uneasy Episcopalian hears the word on Imperial Avenue Salvation Row - An uneasy Episcopalian hears the word on Imperial Avenue

Lester Bangs -The Hardback Lester Bangs -The Hardback

Dots on the Map - Heading East on Old Highway 80 Dots on the Map - Heading East on Old Highway 80

Silents Were Golden - Why early filmmakers zoomed in on San Diego Silents Were Golden - Why early filmmakers zoomed in on San Diego

Where Wild Things Were- Something is lost when something is built Where Wild Things Were- Something is lost when something is built

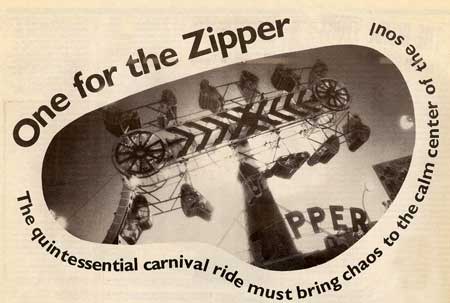

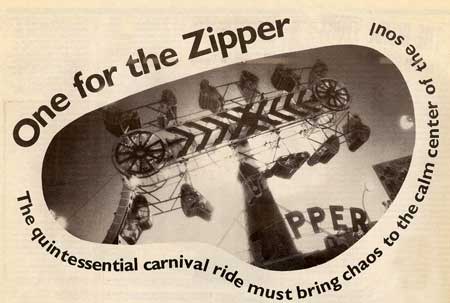

One for the Zipper- The quintessential carnival ride must bring chaos to the calm center of the soul One for the Zipper- The quintessential carnival ride must bring chaos to the calm center of the soul

Deadhead Redux - No one knows for sure why Grateful Dead fans have such a drive to communicate with each other but they do-and they’ve turned Blair Jackson and Regan McMahon’s “The Golden Road” into the most successful fanzine in the history of the form. Deadhead Redux - No one knows for sure why Grateful Dead fans have such a drive to communicate with each other but they do-and they’ve turned Blair Jackson and Regan McMahon’s “The Golden Road” into the most successful fanzine in the history of the form.

The Last Anniversary - An Altamont Memoir The Last Anniversary - An Altamont Memoir

Desolation Row -The lonesome cry of Jack Kerouac Desolation Row -The lonesome cry of Jack Kerouac

Faster Than a Speeding Mythos: Superman at 50 - Superman at 50: The Persistence of a Legend Faster Than a Speeding Mythos: Superman at 50 - Superman at 50: The Persistence of a Legend

When Art is No Object -The Eloquent Object - At the Oakland Museum, Great Hall, through May 15. When Art is No Object -The Eloquent Object - At the Oakland Museum, Great Hall, through May 15.

“He Wasn’t Dying to Live in L.A.” - Intrepid Journalist’s Last Dispatch Before His Collapse “He Wasn’t Dying to Live in L.A.” - Intrepid Journalist’s Last Dispatch Before His Collapse

Search for Honesty in Post-war Life - Plenty Search for Honesty in Post-war Life - Plenty

Armageddon Averted: Where Will You be on August 16. 1987? - Inside Art Goes to the Frontiers of the Mind Armageddon Averted: Where Will You be on August 16. 1987? - Inside Art Goes to the Frontiers of the Mind

Of Speckle-Faced Rats and Supernovas - Michael McClure Of Speckle-Faced Rats and Supernovas - Michael McClure

George Coates - The Physics of Performance and the Art of Iceskating George Coates - The Physics of Performance and the Art of Iceskating

No Escape from the SOUNDHOUSE - Maryanne Amacher No Escape from the SOUNDHOUSE - Maryanne Amacher

A Pynchon's Time A Pynchon's Time

Grants - State of Art/Art of the State Grants - State of Art/Art of the State

Poetry from Outside the Pale - Allen Ginsberg Poetry from Outside the Pale - Allen Ginsberg

Once Upon a Time - In Berkeley Once Upon a Time - In Berkeley

The poet from Turtle Island - Gary Snyder The poet from Turtle Island - Gary Snyder

Noh Quarter

Joyce Jenkins and the Language Troubles Joyce Jenkins and the Language Troubles

Philip Whalen Philip Whalen

|

|

One for the Zipper

The quintessential carnival ride must bring chaos to the calm center of the soul

Story By ROGER ANDERSON

July 13, 1989

My mode of arrival must decide the matter,

so I ride off on the bucket.

Seated on the bucket, my hands on the handle,

the simplest kind of bridle.

I propel myself with difficulty down the stairs;

but once downstairs my bucket

ascends, superbly, superbly;

camels humbly squatting on the

ground do not rise with more

dignity, shaking themselves under

the sticks of their drivers.

Through the hard frozen streets

we go at a regular canter; often I

am upraised as high as the first

story of a house; never do I sink

as low as the house doors.

— Franz Kafka,

"The Bucket Rider"

photos by

Dave Allen

It takes a long time to talk myself into going on the Zipper — a lot longer than it takes me to talk Rob into going with me. I've got to hand it to him: even though he went through the extreme pain of passing a kidney stone a couple of days ago, he's game. The only reason I can cite for my hesitation about going on the damn thing (apart from general cowardice and a rooted distrust of outsized mechanical devices) is that the first time I rode it, almost 20 years ago, I truly believed I was going to die. The Zipper was a new wrinkle on the midway: this big, gleaming apparatus that looked like a gigantic fan belt, with body-hugging cages attached along its length. While the fan belt and the cages (which also revolved on their axes) went whirling around two enormous cogs, the entire length of the mechanism did loop-the-loops. Einstein himself would have been hard-pressed to plot the relative motions involved. Toward the end of my ride in 1970 (and the unit Rob and I are about to enter, all rusted and ramshackle, could very well be the selfsame one), the car I was strapped into seemed to come completely free from its attachments; for a fraction of a second, I was convinced that I was flying through space, that I was about to end my life as a grisly smear on the blacktop. But when the ride came to a stop a moment later, I saw that the ride was intact, nothing out of the ordinary had happened; the operator opened the cage, and I climbed out and went about my business.

That feeling of coming completely unmoored, of hurtling toward death, has never entirely left my central nervous system. So even now — as Rob and I fork over our four coupons apiece (cash equivalent: two bucks) and are loaded into one of the cages — my pulse fibrillates, and I have a powerful urge to call the whole thing off. But rap music pounds out of the Zipper's speaker system at such high decibels that I'd just about have to scream my head off to catch the attention of the large, serene-looking black fellow shutting the cagework door in on us; the skinny, sunburned white guy manning the controls and bopping to the beat seems oblivious to everything except the music and the esoteric knobs and levers poking out of the panel in front of him. So I decide — rather bravely, I think — to tough it out.

Once the door has been latched into place, the cagework car seems awfully cramped; plastic-cushioned metal surfaces and abutments are intruding into our soft tissues from just about every angle. On the other hand, this gives you the feeling that the machine has a firm grip on your body so you won't be permitted to just thrash around inside the cage willy-nilly and get your skull bashed open once the ride starts whirling. Time now to puzzle over the absence of a control wheel that I could swear I remember as a component of the cage interior back in '70; my memory is that by operating that wheel, the rider caused the car to revolve on its axis — or not revolve, depending on your preference. No wheel here, though.

"I get it," I say as the car lurches, and we go up a notch and then stop as a couple of kids are packed into the next cage. "Yeah, I see. You don't need the wheel, you just rock the car back and forth with your weight till it starts tumbling around."

Rob looks at me funny — he doesn't have the faintest idea what I'm babbling about — and suddenly the cage goes shooting up to the top of the conveyer-belt apparatus, stops, and we're swinging back and forth high above the ground.

"This is cool:' I say. "This is okay. This isn't so bad. See, the fact that you're inside this cage makes you feel more secure."

"Right," Rob says. "The cage keeps you packed in nice and tight so that if the ride goes flying apart, you'll get crushed to death first thing instead of being thrown free."

"Now you're getting the idea."

As the ride moves up and down and around by notches so that passengers can be strapped into each car, Rob and I absently rock the cage back and forth. Then, rather abruptly, the Zipper takes off full blast, and we're swooping at fearsome velocities through space. We both instinctively stop rocking.

"I find myself suddenly becoming interested in the concept of structural engineering," Rob yells.

"Right:' I yell back. "For instance, the spot welding on these joints outside the car looks like kind of a rush job. Also, have you noticed how similar these cages are to the utility elevators you see on construction sites?"

A moment later we lurch to a stop at the top of the belt. "Really," I say again, "being up here isn't so bad."

"Yeah, we're farther away from the speakers, so the rap music isn't quite as loud."

Suddenly the Zipper kicks into action again, this time in the opposite direction.

"If this knocks loose another kidney stone, I'll never forgive you:' Rob warns.

"Think of it as a giant salad spinner, a salad spinner made out of rusted metal," I tell him. "It's like you take it in each direction so as to make sure all the water gets thrown off."

Finally we decelerate through a stop-and-start rotation back to ground level, the black guy stills the car's residual movement with one hand and unlatches the cage door with the other, and Rob and I hobble down the ramp. I'm a bit dizzy but euphoric that I've managed to emerge unscathed from the huge and mysterious contraption.

They don't call it the midway anymore — another example, probably, of the way language is constantly being stripped of its old resonances and cultural associations and forced into an increasingly literal frame. After all, who knows what a midway is these days? To most the word means a World War II naval battle in the South Pacific or a defunct drive-in theater in Ocean Beach — hardly images likely to attract modem-day thrill-seekers. So now it's called FUN ZONE; at least, that's the rubric emblazoned on an orange banner that flutters above the amusement rides at the Del Mar Fair.

Still, that which we call a midway by any other name is the same astonishing proposition: mammoth machines, aluminum and steel pistons and flywheels and loops and trailing chains with seats on the ends of them and soaring cagework, incredible masses of metal zooming through the air, with light bulbs and weird filigree barnacling every surface with exotic symbolism ... gigantic portable mechanisms that were torn down in the last city, collapsed onto trailers and schlepped to this spot and reassembled; and a little later, the first fairgoers of the year started trickling in, paying two bucks a pop to let some guy strap them into a cage or teetery car and swing them through the air in unthinkable arcs and parabolas and ellipses like so many Alan Shepards bound for suborbital flight — not to win the space race or close the missile gap or even come up with a safer way to construct an automobile, but (to put it in the concisest terms) to make waves in their inner-ear fluid.

The inner ear tells your brain which position your body is in with relation to gravity. It might best be described as Mother Nature's template for the carpenter's level. When an amusement ride sends you flying through space in a series of interlocking trajectories, even if you're smart enough to keep your eyes closed (but stupid enough to get on the ride in the first place), the fluid in your inner ear canal goes spattering, scrambling your body/space orientation and, presumably, providing you with a thrill that's well worth the money you spent for the privilege. In a very real sense, then, those glittering, multi-ton machines you see every year at the fair were designed for the sole purpose of creating these almost microscopic neural tsunamis.

The potential of self-driven machines to wreak such stimulating havoc in the inner ear is a kind of ironic consolation prize of the Industrial Revolution. It must have become evident at a fairly early point — perhaps as early as Thomas Fulton's historic 1807 steamboat ride up the Hudson River — that being powered through space was not just convenient and profitable but also fun. That's why, today, we have not only airplanes and busses and trains and space shuttles but dirt bikes and racing cars and carnival rides.

Indeed, a bonus value of the Fun Zone is that it is, in many ways, a traveling demonstration of the basic principles underlying the Industrial Revolution, preserving them, as it were, in a drop of amber. You can look at most amusement rides and easily trace their design origins to certain 19th-century industrial innovations. Who, after all, was the true inventor of the bumper car, if not Henry Ford? By the same token, the roller coaster is nothing more than steam-rail travel with its "travel" component eliminated (you don't really go anywhere) and its bothersome vicissitudes (I have the pleasure of giving the word its literal application) exponentially enhanced. The first Ferris wheel was constructed for the 1893 Chicago World Expo by an American bridge builder named George Washington Gales Ferris, who, strangely enough, saw his brainchild as America's response to the engineering challenge posed by the construction of the Eiffel Tower in Paris.

A bit less impressively, the fundamental concepts behind some rides were expropriated from children's playgrounds -another sphere in which the inner ear has traditionally received a more or less salubrious workout. Everywhere you look during your visit to the Fun Zone, you see swings and slides and — yes -merry-go-rounds puffed up to Brobdingnagian proportions and driven by powerful engines. A popular ride called Pirate, for example, is modeled on the swing. This is not to say that going on it is child's play, although at rest it looks deceptively low-key. A huge piece of metal shaped like a sailing ship is suspended by shafts; people are seated in rows across the ship, passengers toward one end facing the other end and vice versa. Once everyone is thoroughly strapped in, the operator throws a switch and the ship moves back and forth like a swing; the bow slides up into the air, the ship swings back, the stern slides up into the air and back; the arc gets wider and wider till it reaches a full 180 degrees and the people strapped inside the ship are absolutely parallel with the ground (which is, one can't help reflecting, very hard and unyielding). All of this looks, as I say, like a fairly easygoing proposition. But at the top of each 180-degree arc, the ship pauses for a millisecond — a millisecond during which you can feel your guts and your spine and your pancreas and your brain and, yes, your inner-ear fluid heeding the call of gravity and evincing an irresistible desire to drop down onto that unyielding asphalt.

The economic advantage to Pirate is that you don't have to go on it to find out how terrifying it is. As long as you're observing it from in front, everything seems fine; but if you stand under the ship at one end of its arc and look upward as it swings by, watch it heave itself into the sky in pursuit moving bodies, and see it pause for that millisecond directly above you — this odd-shaped planetoid weighing certainly a couple of tons — your nerve endings will get the message: if the damn thing were to come loose from its hinges, not only would the people inside it get atomized in the blink of an eye but the cleanup squad wouldn't even need a body bag to take you away.

* * *

When Barbara was about ten, she went to a church fair and rode a contraption called the Scrambler, which consisted of a lot of cars hooked to the end of shafts that moved and shifted among each other on a level plane, a sort of robotic square dance at high speed; the cars always seemed like they were about to collide but missed each other by a few inches to go swooping on to the next close call, and the next. So little Barbara climbed into this thing, and the operator lowered the safety bar, and the ride started up and accelerated, and the next thing she knew she was getting thrown around inside the car like a test-crash dummy. Her body was too small to get a purchase on the car's interior; her legs were bouncing all over the place, and her arms were too short to get an effective grip on the safety bar. Today, she remembers thinking in that strangely collected manner familiar to accident and crime victims — that once she had been bounced out of the car, her first priority would be to lie as flat on the ground as possible so that the other car could pass over without mangling her.

Luckily, the operator noticed what was happening in her car and quickly brought the machine to a halt. "The funny thing was," Barbara recalls, "the other people on the ride seemed annoyed with me for ruining their fun."

Now Barbara is a grown-up with a daughter of her own -Elizabeth, who is nine. And here the three of us are wandering around the Fun Zone looking for cheap mechanical thrills. One of the first rides we observe is almost a dead ringer for the Scrambler that Barbara remembers so well; and as we watch it go through its paces, we notice that a little girl in one of the cars is having the same problem Barbara experienced at the long-ago church fair. The operator sees the child's distress, stops the ride, directs his second banana to get into the car with the girl and hold her steady, boots the mechanism back into action, and continues it on its program of near-collisions.

Farther along, Elizabeth spots a miniature roller coaster ride called the Hi Miler — identical in all but name to the ubiquitous Wild Mouse. Miniature it may be, but it still whips people around banked curves at speeds that make them think their spines are going to snap in two. For a moment, Elizabeth seems determined to go on it — somewhat to her mother's chagrin, because the ride is dramatic and powerful enough that she can't, in good conscience, allow her daughter to go unaccompanied. I toy with the idea of volunteering to take Barbara's place but decide that, in this feminist age, such gallantry would be tantamount to chauvinism and, therefore, not appropriate. So Barbara remarking that "I'd rather have someone run a spear through my left shoulder" — gets in line with Elizabeth. As the line nears the gate, Elizabeth begins to have second thoughts. "I want to think it over," she tells Barbara solemnly, and they both withdraw. It goes without saying that the more you think something like this over, the less likely it is you'll be foolish enough to follow through. Barbara is saved.

Right next to the Hi Miler is a ride with no name: peer as we might into the complicated stippling of light bulbs and raised metal designs that cover its surface, Barbara and I can't see a name anywhere. This is an ominous touch; but otherwise, the ride seems well below midpoint on the terror scale. Pursuing some kind of "Surf's up!" theme (to judge by its filigree symbolism of waves and sun and beaches), it consists of one long car that moves in a wavy circle around a track; riders are seated so they face backward as they go crashing about the circuit. No big deal. Elizabeth gets on, and Barbara and I feel few compunctions about letting her ride alone. Soon there are enough customers to justify a go-round, and the operator sets the ride in motion. The interesting fillip here is that after the ride has gathered a good head of steam, the operator hits a toggle that causes a black tarp, previously furled along the inside rim of the car, to go shooting up and over the passengers, completely enclosing them. A moment later, he makes the tarp furl back into its original position, then repeats the action. During the moments when we can see her, Elizabeth is grimly clutching the safety bar with a determined look on her face.

"She isn't enjoying this at all," Barbara comments resignedly.

"That tarp thing seems a little chancy," I observe. "Like, what if it got snagged on something — or someone?"

"It's the sort of thing you're better off not thinking about too much, I guess," Barbara sighs.

* * *

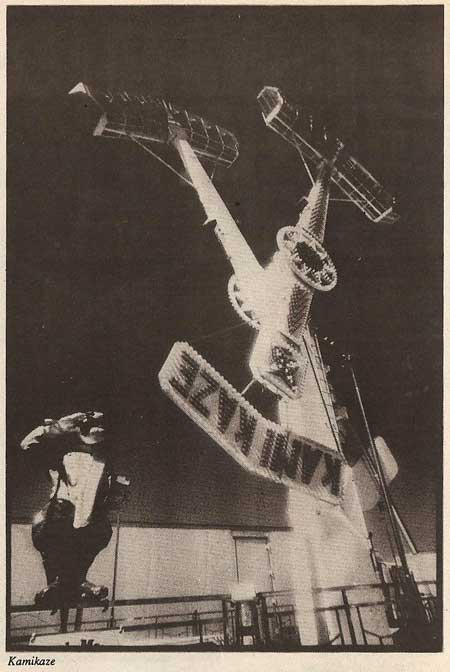

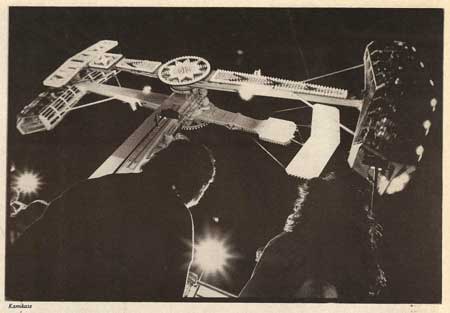

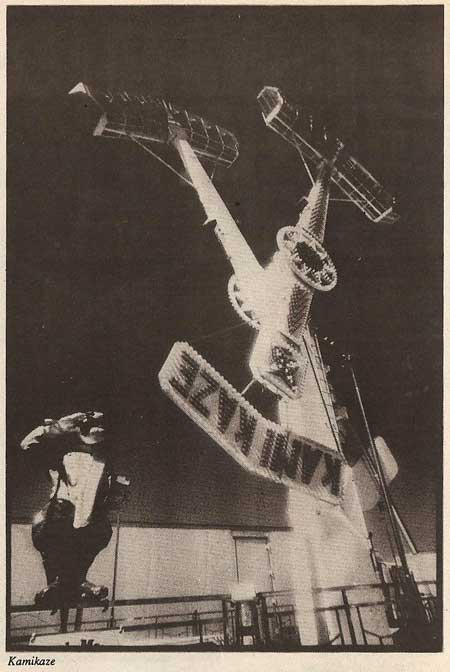

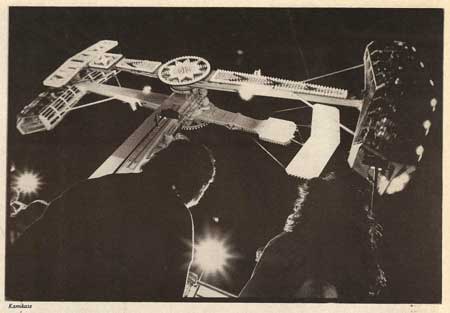

When I was growing up and attending county fairs, the ne plus ultra of carnival rides was the Hammer — an exceedingly scary machine consisting of twin shafts with revolving cars attached to each end that would crash past each other; riders were buffeted about in spirals. In one scene in the movie Under the Volcano, set in Mexico in the late '30s, Albert Finney gets on a Hammer-type ride at a Day of the Dead carnival. Extremely inebriated, he was sent caroming around inside the car like a rag doll. Director John Huston is well known for his conscientious research, so I'm confident that the Hammer — or something closely resembling it — existed at this early point. Today you can probably search a given carnival from one end to the other without finding a surviving example of this piece of nefarious machinery; but that doesn't mean it has disappeared. It has simply been upgraded and transformed into more powerful, more imposing forms of structural derring-do — for instance, here at the Fun Zone, a ride called Kamikaze.

The ride's name presents a challenge that I, for one, will gladly take lying down: all the money in the world couldn't induce me to actually clamber aboard this thing, even though, at rest — like Pirate — it doesn't look like any big deal. What you see are two gigantic shafts standing at right angles to the ground; attached to the lower end of each shaft is a large car, capable of seating 16 people, each car enclosed at the top by a cage. As passengers file on, the ride seems to be of fairly modest proportions simply because: (1) it isn't moving, and (2) with the cars resting on the ground, the full height of its arc isn't apparent. Once everyone is tightly screwed in, the operator makes the shafts swing — one car going this way, the other that way. Like Pirate, the arc increases bit by bit; unlike Pirate, it doesn't reach its maximum effectiveness at 180 degrees — indeed, at 180 degrees the "fun" has barely started. The shafts accelerate, the arc increases past the 180-degree mark, and the cars swoop through the air in full circles, an unbroken 360-degree course, passing each other by a hair's breadth at the very top. If that millisecond's pause at the top of the Pirate course seemed troubling, consider this: the Kamikaze operator makes these two cars come to a full stop at the very top of the circle, so the passengers hang upside down in the blue sky, with only straps and safety bars preventing them from falling onto the cagework ceiling and only the cagework keeping them from falling to the unyielding ground. Then the cars are allowed gently to start sliding back down the circle in the opposite direction, so that passengers who were swooping face-front a moment ago are now traveling backward; more acceleration is laid on, and the machinery gives off a rising whine that you probably will want to believe is all part of the show. Then the cars are brought to a halt at the top of the circle again. From down here, I see ocean mist drifting in curlicues through the summer blue and imagine that it will waft in through the cage, depositing moisture on the passengers, cooling them off a bit in preparation for one last suicidal career through empty space before the cars are allowed to submit to gravity, decrease their arcs, come to a halt at the bottom, and disgorge their victims.

* * *

At smaller fairs and parking-lot carnivals, the rides usually belong to and are maintained and operated by a single traveling amusement company or "show"; at a major event like the Del Mar Fair, several such companies come together, each bringing a handful of mechanical diversions, and set up shop in competition with one another. Each company employs a number of permanent workers who travel with the show from fair to fair (temporary, spot help for minor jobs is picked up in each city). You see these guys every year — skinny, shaggy, blue-collar types, with wraparound shades perched on sunburned noses; they smoke a lot and seem pretty tough and unforthcoming.

Steve Cimino, a full-time worker, has been with B&B amusements since 1985, when the show played a carnival in his home town of Santa Maria, and Steve, at the time, about 20 years old and out of work, was hired on just to help tear down the bumper-car ride. Steve wangled a permanent berth with B&B and within a few months became foreman of the show's bumper-car team. Today, he crisscrosses six Western states nine months of the year with B&B, serving as an operator on the Gravitron, the Himalaya, and other rides, including the Zipper. When I finally get a chance to chat with him, he's about to go on a break and is perfectly willing to tell me whatever I might like to know. First, I ask him what happened to his black partner, working the Zipper with him. He is now nowhere in evidence.

"I had to fire him off the ride," Steve explains, lighting a cigarette. "I mean, I didn't fire him; my boss did. See, it's real important on these rides to always be paying attention to what's going on. Now, the Zipper has this tendency, when you're loading people on it, to shift up a little bit; the weight of the people makes the chain move up a notch — and if you're not on the lookout for that, one of those cars can hit someone on the head. So this guy, I had to keep yelling at him to watch what was going on. I finally decided he wasn't interested enough in taking care of business, so I talked to my boss, and my boss fired him off the ride. He's still with the show, though; he's just working a different job.

"Our show has two Zippers, two Gravitrons, two Tilt-0-Whirls, a Himalaya, an Orbiter, two Loop-O-Planes, a Sea Dragon, a new ride called the Global Wheel, a Round Up, and an SDC Coaster we bought used and rebuilt in winter quarters, which is in Yuma. Two months out of every year, we're in winter quarters, rebuilding and repainting the rides. This winter we also rebuilt the Zippers and the Sea Dragon — but really, we work on all the rides, rebuilding and repainting them. Every year the owner has to get a license for each ride that allows him to keep operating it.

"Most of the rides are mounted on trailers; at the end of a fair, you tear 'em down, collapse 'em onto the bed, pack 'em up, and a big rig hauls 'em to the next show. The people who work on the show hitch rides with the truck drivers, or else they drive their own cars from fair to fair. Hardly anyone ever gets stranded. Most of the jumps from one town to another aren't that long; the longest jump we've got to make this year is a pretty big one, though, from Lancaster [California] to Salt Lake City.

"It takes something like four hours to assemble the Zipper, which is about average for that kind of ride. Kiddy rides usually take less time, but a roller coaster'll take you a day and a half. Every morning an inspector comes around and signs off your inspection sheet so you can keep running; and there are safety meetings for all the operators once a week, where the inspectors warn you about stuff you may be doing wrong and bring you up to date on accidents that have happened you may not have heard about and how they could have been prevented. Me, I have a pretty good safety record. I've had people get little cuts and scrapes, but that's about it -nothing major. Sometimes I'll see someone hanging around the ride, you know, like they want to go on it but they don't want to go on it. And I'll tell 'em, 'Hey, go ahead and try it, and if you don't like it, I'll stop.' It's no big thing; I stop the ride for people all the time.

"When we're at a fair, we're all pretty much on our own when it comes to eating and sleeping and all that. Some fairgrounds, if you want to take a shower, you have to use a hose or something. Here we've got it pretty good, because the races aren't on and so they let us use the jockey quarters over by the track for showers and stuff. We eat whatever we can get, which usually means buying food at the concessions — which is kind of a drag, because the food's expensive, and it's not that great for you; you end up eating a lot of hot dogs. Sometimes I like to leave the fair and eat at a restaurant, like a Denny's or someplace, but we're kept pretty busy, and so it's hard to get the time away.

"Some of the workers have mobile homes they tow from one fair to the next, but I sleep on my ride. Sometimes I stay in a motel, but that's a luxury. Here, I'm sleeping on the Zipper every night. Which is okay, because then when I get up, I can take care of the ride first thing — keep it lit, keep it running. Because you want to have the ride ready to roll when the fair opens for the day. Like, if I'm still fiddling with the bulbs and that other Zipper is taking in all kinds of money — it belongs to another show — my boss'll come over and say, 'Why aren't you open yet?' It's not like he's trying to rush me; he wants the ride to be in good shape, too. It's just that you need to get it lit, get it open, keep it running.

"I used to go on carnival rides the whole time I was growing up, and I still do. Kamikaze? Sure, I've been on it. There really aren't any rides I'm afraid to go on or wouldn't go on. The only rides I won't go on are like the fun house and glass house rides — not because they're scary or I don't think they're safe, they just don't interest me.

"It's a hard life, I can tell you chat," he goes on. "I mean, it's a good life — you get a lot of freedom — but you have to work long hours, and the pay isn't much. Me, I make $225 a week nine months out of the year. That's okay, though. A lot of people complain about the money, but I figure the main thing is, we're here to do a good job and show people a good time. If the people are having fun, then I'm having fun."

Later, I catch sight of Steve working the Himalaya, which is a lot like the ride with no name that Elizabeth went on, except that instead of a tarp springing out at the operator's whim, the car simply glides through a tunnel on the back stretch for a less capricious night-and-day effect. I see now that when he's working a ride, Steve is always in motion. On the Zipper, he's bopping at the control panel; here, his long, rubbery limbs and torso are constantly moving, flexing, almost dancing to the blast of music from the speaker system and to the rhythm of the unseen gears and gizmos and driveshafts and sprockets. He goes daddy-long-legging up and down the ramp while the passengers are climbing on, he slaps a hand on the safety bars to ensure that they're clapped on tight; then one of his skinny arms with a spidery hand snakes behind him toward the onlookers and flutters in a come-hither way, as though to say, "Come on, come on, plenty more room." Then the ride starts, slowly at first, and he stands, legs sprawled out, slapping each car as it passes by, slapping each safety bar; his free arm snakes out behind him to beckon onlookers for the next go-round. As the ride gathers speed, he slaps, slaps, slaps, and I'm trying to remember what this reminds me of, and then I've got it: he's like a bigger kid taking care of younger kids on one of those public-park merry-go-rounds made of cast iron; the bigger kid slaps the bars of the contraption, pushes, pushes, accelerates the mechanism until it's going too fast and he has to stop slapping it or wreck his hands.

* * *

I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked, dragging themselves down the negro streets at dawn looking for an angry fix, angeiheaded hipsters crooning for that ancient heavenly connection to the starry dynamo in the machinery of night....What sphinx of cement and aluminum bashed open their skulls and ate up their brains and imagination?

Moloch! Moloch!

— Allen Ginsberg, "Howl"

As the sun passes through the gathering coastal mist toward the sea, and darkness spreads from the Fun Zone shadows, more and more people are getting off work or finishing their weekend errands and collecting the kids and motoring out to Del Mar and jamming their way into the parking lot and riding the jitney bus to the nearest fairgrounds entrance and ambling down past the Don Diego clock tower to the Fun Zone and purchasing coupons and lining up in front of the rides and actually climbing onto them, and the operators are therefore having less occasion to let their machines stand idle; so the rides are looping and bursting and arcing and accelerating and ricocheting and near-colliding almost nonstop. This is when the Fun Zone is revealed most especially to be an encampment of insane machinery: you look around and see gigantic phalanges and pistons and throw rods and flywheels turreting and spinning, amid a cacophony of high-volume pop music and engine noise that would make Charles Ives himself cringe.

When night falls, the strings and swirls and kaleidoscopes of electric bulbs festooned on the spokes and wheels and rims and bulkheads of the rides, rather than illuminating the machines to which they're attached, make them almost invisible — your eyes become hypnotically fixed on the lights themselves, and the metal structures they clothe are nothing but dark gravitational fields that make oblique and highly ominous impressions on the senses. It's as though a star had gone dead at its core, leaving only a thin magmatic crust of flame gouts as a reminder of its existence.

It's also like that scene in Fritz Lang's Metropolis, where the factories and smokestacks and filing workers coalesce into a death's-head Moloch visage. In the nighttime Fun Zone, screams burst in great waves from the invisible, swooping enclosed spaces of the rides while multicolored electricity burns in streamers. There's something definitively insane going on here; it's almost enough to turn you Amish. Here's the demonic, hubristic impulse behind the Industrial Revolution laid bare, caught in a drop of amber. Not once have I concerned myself with the particulars of "safety" for when it comes to brainless but powerful machines, airplanes or automobiles or carnival rides, under even the most painstaking circumstances, safety becomes a concept so relative as to be meaningless and, if you're in the mood for gallows humor, laughable. With carnival rides, it seems impossible that any greater care is taken to ensure that they're "safe" than is taken with passenger airplanes; and how many weeks go by that you don't pick up the daily rag and read all about one of those shearing off a wing and plunging to the cold hard ground, with no survivors? Or a rogue train plowing through a block of houses? The Industrial Revolution gave mankind a robot twin for life, a dumb nuts-and-bolts Gargantua who generally does as he is bid but demonstrates again and again that he has a haywire, utterly unpredictable life of his own. Here in the Fun Zone, we elect to disport ourselves carelessly with this twin and damn the consequences (full speed ahead).

And here are some forlorn souls standing in front of Kamikaze watching their loved ones fly bleating through the empty night: a riot of electricity glares across their upturned, anxious faces, and if you didn't know better, you might think they were watching an airliner glide into a row of buildings.

back to top

|